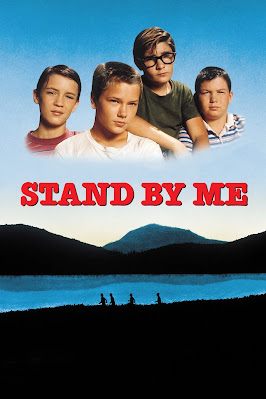

Deranged (1974)

On the morning of November 16th, 1957, Bernice Worden, the 58-year-old owner of a hardware store in Plainfield, Wisconsin, disappeared without a trace. Her son, Deputy Sheriff Frank Worden, entered the store around 5:00 p.m. to discover the cash register open and blood stains on the floor. Worden informed investigators that, on the evening prior to his mother's disappearance, Ed Gein, a 51-year-old farmer, known by the townspeople as a timid and somewhat strange but overall harmless little man living alone in the farmhouse in which he was raised, had visited the store and was expected to return the following morning for a gallon of antifreeze. A sales slip for that antifreeze was the final receipt written by Worden on the morning of her disappearance.

Later that evening, Gein was arrested at a West Plainfield grocery store, and as the Waushara County Sheriff's Department searched his farm, a sheriff's deputy discovered Worden's decapitated body in a shed, hung upside down by her legs with a crossbar at her ankles and ropes at her wrists. Her innards had been systematically removed, her torso described as "dressed out like a deer." She had been shot with a .22-caliber rifle, and the mutilations were inflicted postmortem. Searching the house, authorities came across a artifacts seemingly conjured from the bowels of hell: whole human bones and fragments, a wastebasket made of human skin, human skin covering several chairs, skulls on Ed's bedposts, female skulls, some with the tops sawn off, bowls crafted from human skulls, a lampshade made from the skin of a human face, Bernice Worden's head in a burlap sack, and no shortage of plenty of other atrocities.

Pleading not guilty by reason of insanity, Ed Gein was found competent enough to stand trial and was sentenced to spend the rest of his life in a mental hospital for the criminally insane, where he died at the age of 77 due to respiratory failure, secondary to lung cancer. In addition to the murder and dismemberment of Worden, Gein also confessed to the murder of 51-year-old tavern owner Mary Hogan in 1954, and admitted to exhuming the corpses of freshly buried middle-aged women who reminded him of his fanatical mother, Augusta.

Nearly 70 years later, Ed Gein's short-lived but shocking murder spree remains one of the most vile, reprehensible, and stomach-churning examples of the violent underbelly of human society, and has served as the inspiration for a handful of some of the most iconic serial killers in horror movie history. In 1959, author Robert Bloch was the first to exploit this story as the jumping-off point for his horror novel, Psycho, adapted that same year for film by director Alfred Hitchcock and screenwriter Joseph Stefano, revolving around the young, sexually repressed proprietor of a secluded motel who preserves the decomposed corpse of his long-dead mother and dons the dress she was buried in, along with a wig, to murder any women to whom he feels an attraction. In 1973, Tobe Hooper and Kim Henkel took a more freewheeling approach to the story for the authoritative teen slasher, The Texas Chainsaw Massacre, in which a group of young adults taking a road trip through Texas on a sunny Saturday run afoul of an entire family of sadistic cannibals who decorate their farmhouse with the flesh and bones of anyone unlucky enough to cross their path. But the greatest use of Ed's crimes wouldn't emerge until 1991, in the currently final film to walk away with the Oscar grand slam, Jonathan Demme's psychological horror masterpiece, The Silence of the Lambs. Buffalo Bill, a misogynistic serial killer still on the loose, abducts young, overweight women, Ted Bundy-style, and enslaves them in the dry well hidden in his basement, starving them for three days before shooting and skinning them to create a "woman suit" in order to escape his own identity.

While the aforementioned trio of genre classics remains the most popular to utilize this real-life madman, there is one more film that very few seem to know about or include in the conversation about horror films inspired by Ed Gein. One that is the most faithful in detail to the original story from which it spawned, so much so that it's more "based" on it rather than merely "inspired." Unfortunately, it's with good reason that this particular movie is largely forgotten and has only five reviews on Rotten Tomatoes, along with a mediocre 40% approval rating. The fittingly uninspired title of said under-seen film is Deranged, a bland, largely fictionalized retelling of one of the most ghastly crimes in the annals of American history, distinguished by a single suspenseful set piece and a memorable lead performance, however weighed down with unnecessarily expository onscreen narration and neutered by a lack of graphic gore.

In the spirit of John Larroquette's fabricated but effectively haunting narration at the beginning of Texas Chainsaw, Deranged commences with a title card declaring that the events we're about to witness are "absolutely true," claiming that only the names and locations have been altered. Unfortunately, this attempt at a mood-setter is proven embarrassingly false by a misguidedly campy undertone, increasingly preposterous plot developments, stolen character details, and a sensationalistic approach to its antagonist's murder spree.

In an undisclosed time period, like the 1950s as when its origin story transpired, middle-aged Ezra Cobb (Roberts Blossom) lives in a farmhouse in the rural Midwest with his mother, Amanda (Cosette Lee), a misogynistic religious fanatic slowly dying of an indeterminate illness. As we learn from Tom Simms (Leslie Carlson), a newspaper columnist who appears onscreen from time to time to deliver non-diegetic narration, Ezra's father passed away ten years ago, so Amanda has become his entire world, his best friend, and single source of human contact and comfort, dubious as the latter may be. While feeding his bedridden mother one day, Ezra's ears are bombarded with sermon-like proclamations of the evils of women (except for perfect Amanda, of course). "The wages of sin are gonorhhea, syphilis, and death" Amanda screams, insisting that once she dies, women will try to take advantage of Ezra and rob him of his money as well as his virginity. As Ezra tries to calm her nerves with a bowl of soup, Amanda succumbs to her illness, leaving a heartbroken Ezra all alone.

Like Ed, Ezra preserves the upstairs bedroom where his mother slept, and continues living in his childhood home under the delusion that Amanda is "just sleeping." Almost a year later, haunted by the auditory hallucinations of his mother begging him to free her from the cold darkness of her grave, Ezra drives out to the cemetery where she's buried, digs up her decomposed body, and returns it to their home, cobbling her back together with discarded fish skin and wax. He speaks to his mother's corpse as though she were still alive, and once he learns about the advantages of an obituary, begins exhuming the graves of other middle-aged women to keep himself and his mother company. However, as narrator Simms needlessly but ominously forewarns, the company of already-deceased people can only sustain Ezra's obsession for so long before he develops a thirst for the blood, flesh, and bones of the living.

Deranged marks the solo directorial outing of Jeff Gillen, a small-time actor from a handful of movies prior to his death in 1995. Most notably, he portrayed the mall-store Santa Claus in the 1983 holiday heart-warmer, A Christmas Story, in which he delivered the immortal line to the young BB gun-obsessed Peter Billingsley, "You'll shoot your eye out, kid." Based on his work in this 1974 psychological slasher, it's probably for the best this was his first and last time behind the camera. Directing from a screenplay by his co-director, Alan Ormsby, neither filmmaker displays much of a gift in this crucial department, as their direction is mostly unremarkable. Gillen and Ormsby use a noticeable number of two shots in filming their scenes, such as in the opening where Ezra visits his dying mother in bed, and during the seance between Ezra and Maureen Selby (Marian Waldman), the only woman Amanda deems worthy of her son solely on account of her undesirable weight. However, the directors do get a little creative for the abduction scene of Sally Mae (Pat Orr), the teenage girlfriend of the son of Ezra's next-door neighbor. As Ezra aims a rifle at the cashier, obliviously reading a book, her face is shown from its ocular lens. When Sally looks up and politely asks Ezra what he's doing, the directors put us in the perspective of the predator, his rife slowly rising into the frame.

Producer Tom Karr, who had held a years' long fascination for Ed Gein, funded Deranged himself using income he had earned as a concert promoter for Led Zeppelin and Three Dog Night, ultimately filming on a budget of $200,000. It seems that wasn't quite enough to secure a professional-looking aesthetic for the film, as certain scenes like the funeral for Amanda Cobb underscore the low budget at work. As Ezra sits in agony before his mother's open casket in a dimly lit chapel that might as well be Gillen's living room, the only two attendees are his next-door neighbors and only acquaintances, Harlon and Jenny Kootz (Robert Warner and Marcia Diamond). Cinematographer Jack McGowan films the trio of actors in a three shot, placing the camera statically behind their seats, the lifeless face of Amanda slightly visible in the background. Based on Amanda's hateful and self-righteous demeanor, it's no surprise her funeral isn't overcrowded with mourners besides her son, but it still seems unlikely that she has no friends or family who would show up to pay their respects to both her and Ezra. (In a ridiculous throwaway line of exposition, Harlon randomly whispers in Ezra's ear that Amanda, in addition to being a very good woman, was also "very religious," as if both Ezra and the audience hadn't already pieced that one together by now.)

Ormsby attempts to examine the damaged and emotionally crippled psyche of his demented anti-heroic protagonist, shedding a light on the cause of his approaching descent into morbid madness and contrasting the inhumane abhorrence of his future atrocities with the universally human pain of his unimaginable loss. Unfortunately, his digging for empathy and compassion lands as flatly as a pancake because the relationship between Ezra and Amanda is only perfunctorily illustrated in a single scene at the beginning. We see Ezra as a devoted son, bringing a freshly hot bowl of pea soup to his dying mother as she lies suffering in bed. He tries to spoon-feed her, but she wants nothing to do with food. Instead, bitter over her miserable, lonely existence and counting the seconds until she meets her maker and greatest inspiration, Amanda goes on a tirade about women, the last of probably a lifetime's worth. She describes them as greedy, untrustworthy, and inherently sinful, transferring her misguided, self-loathing misogyny onto her impressionable and overly dependent son, and urges him to remain a virgin for fear of catching a sexually transmitted disease.

Unlike his source of inspiration, Ezra doesn't seem to have any siblings who could argue against Amanda's tainted worldview, and Ormsby doesn't care to dive into his character's childhood for further context. All we get of Ezra's upbringing is suggested in this introduction, and it isn't enough. Amanda is portrayed in a most grotesque light, a one-dimensional religious fanatic and hypocrite who hates all women, excluding herself, and likely shared an incestuous relationship with her sexually repressed man-child of a son. As a result, any attempt at poignancy for Ezra's situation is futile, as Amanda's sudden death registers more as silly and long-overdue than the harrowing nightmare it's intended to be. Who could feel pity for such a toxic and hateful zealot? As Ezra begins to force-feed his mother spoonfuls of pea soup, the vomit-like green spilling all over her mouth is superseded by a spontaneous outpouring of blood, and the mixture of green and red, Ezra's ignorance, and Amanda's cartoonish ravings produce more chuckles than tears. Aside from the failed emotional impact, what disease makes someone randomly vomit blood seconds before they die? It just feels like a melodramatic flourish employed only to increase the shock value of the scene.

Following his titular stint as Ezra Cobb, Roberts Blossom wouldn't receive his most notable role for another 16 years, playing the outwardly menacing but deceptively good-hearted neighbor, Old Man Marley, in Home Alone. In hindsight, it seems fitting that he got his start playing a grave-robbing, woman-skinning serial killer. Bearing a striking resemblance to Robert Duvall, with whom he nearly even shares a first name, Blossom delivers a pretty good lead performance, utilizing his bulging eyes, jutted lower lip, and a creepy, absentminded smile to convey Ezra's emotionally and intellectually stunted mindset. Even without having witnessed Ezra's backstory, which could only be filled with physical, psychological, and possibly sexual abuse at the hands of his parents, Blossom portrays Cobb as a well-intentioned, immature, isolated little boy trapped in the body of a middle-aged man. His body has naturally grown, but his brain and emotions are still those belonging to a child who never learned how to grow up, interact with other people, or take care of himself. All he knows is the misogynistic vitriol his mother has spewed and indoctrinated every day throughout his life, and Blossom makes his confusion, heartbreak, and codependency believable, if not especially moving. His performance may not quite measure up to the poignant craving for human connection emanated by Anthony Perkins, the spine-chilling, balls-to-the-wall insanity of every Sawyer family actor, or the balancing of inhumane sadism and heartbreaking vulnerability exhibited by Ted Levine. Nonetheless, Blossom inhabits the skin of Ezra (and the numerous women he unearths from the grave) with enough presence and role commitment to hold our attention even as the buildup fails to generate a sensation of dread and nothing particularly horrifying or visceral is offered up on the screen.

In addition to sharing a close age range with his source cannibal (Blossom was around 48 at the time of principal photography), as well as possessing a similarly slender build and gregarious, open-hearted face, Blossom is costumed in a commendably identical outfit to the one infamously worn by Ed Gein: a red plaid flannel shirt jacket and a flat cap, worn primarily in outdoor scenes when Ezra is working on his farm or digging up recently buried bodies in the dead of night. For interior scenes set within the confines of his dirty, desolate homestead, Blossom frequently wears a white button-down shirt with suspenders, accentuating Ezra's conservative and deceptively wholesome personality, all the better to lull his trusting victims into a false sense of security. Surely a man of God who dresses neatly and in adorable suspenders couldn't be capable of any harm, right? This buttoned-down appearance will soon be contrasted horrifically with the sight of Ezra putting on the skin of a dead woman's face and talking to his mother's corpse through its lips.

Unlike in The Texas Chainsaw Massacre, in which John Larroquette's narration was heard over a black screen, accompanied by the written text of his spoken words, before disappearing for the remainder of the experience, Gillen and Ormsby make the baffling, not to mention distracting, decision to cast Leslie Carlson as an onscreen narrator who pops up sporadically to explain aspects of Ezra's life story and forewarn audiences of the mind-boggling grotesqueries that lie in store. Admittedly, Carlson's appropriately solemn and measured delivery feeds into the gritty, documentarian verisimilitude for which the filmmakers are striving and that imbued Texas Chainsaw with an authenticity that distinguishes it from its future slasher brethren. And while he isn't overused, the fact of the matter is the whole movie could have been accomplished without his involvement, which exists only to spell out details the audience would have been smart enough to figure out on their own, and foreshadow plot developments that we all know are coming. The intent is to instill apprehension, but in effect it just rolls the eyes.

Composer Carl Zittrer complements the downbeat ambience of Deranged with a funereal organ score that plays sporadically throughout. While it's a little too repetitive and indistinct to stand out as a memorable piece of genre music, it at least evokes the funeral home scene in The Silence of the Lambs where Clarice is left alone in a room with the skinned corpse of a murder victim and surrounded by a gaggle of scowling, disapproving policemen.

Remember what I said about the opening title card promising that the story to which we're about to bear witness is entirely faithful to the real-life story of Ed Gein? That the only inaccurate details pertain to the names of the characters and locations? Well, here's some bad news. If you're even remotely familiar with the true story from which this is derived, you'll grab hold of numerous inaccuracies apart from just the names. If you go into Deranged knowing absolutely nothing about Ed Gein, his life story, his killing spree, or the fictitious horror movie characters he inadvertently spawned, there's a good chance you'll still catch on to the liberties taken to make the story more "cinematic." For starters, Gillen and Ormsby spoil their own ambition to translate one of the most terrifying real-life horror stories to celluloid by incorporating a campy tone that constantly reminds audiences that they're in the presence of a mere movie. Take the character of Maureen Selby. An overweight widow who recently lost her husband and now lives alone in an apartment, the second she meets Ezra and learns he's the son of her late friend, Amanda, Maureen makes her loneliness-driven attraction pitifully obvious. She seats Ezra down beside her on the couch, and as they converse, Ezra thoughtlessly reveals that he still communicates with his mother. Rather than laughing off that remark as a joke, as the Kootzes invariably do, Maureen takes it seriously, but not in the way you'd expect. "Are you making fun of me?" she sternly asks. When Ezra insists he isn't, Maureen's expression of vague horror and offense gives way to one of pure, unrestrained ecstasy, as she reveals she too has been in contact with her late husband. Unsurprisingly, Maureen is an "original" character, to say the least, not based on either of Gein's two recorded victims. In a single moment of chuckle-worthy black humor, Ezra expresses his concern of Maureen to the mummified corpse of his mother, opining that she isn't altogether there "upstairs." Even for a delusional psychopath like Ezra, Maureen is too eccentric.

Following their first awkward meeting, Maureen invites Ezra on a "date" to conjure the spirit of her deceased husband, during which she begins talking to Ezra in a deeper, masculine voice. As Ezra stares at Maureen, his eyes bugged out in discomfort, Maureen forcefully puts his hands on her breasts and demands, under the feigned possession of her husband, that he provide her the carnal pleasure she's been deprived of for several years. She moans sensuously as Ezra caresses her breasts like a little boy grabbing all the candy he could ever want, and predictably orders him to have sex with her. It's a ruse transparent to everyone except the inexperienced Ezra. The pair relocate to Maureen's bed, where Ezra begins suffering flashbacks to his mother's final proclamations of the sins of female sexuality (even though the woman he's with is the one Amanda gave her blessing for). The cutting back and forth between close-ups of Ezra's petrified face and Amanda's deathbed rant is designed to ratchet up anxiety over what Ezra is getting ready to do, clarifying his earlier comment about bringing along "protection," but the silliness fatally undercuts it.

As for the other two victims in Deranged, their names are Mary Ransum (Micki Moore) and Sally Mae, and they are based almost entirely on the two real-life victims of Gein: Mary Hogan and Bernice Worden. However, aside from one of their names and both their occupations, that's where Ormsby's adherence to facts ends. While Mary Hogan was 51 years old and the owner of a tavern, Ormsby writes Mary Ransum as 17 years younger and a waitress at a tavern. Bernice Worden was 58 and owned a hardware store; Sally Mae is a teenager, and works as a cashier at a hardware store. The ages of Hogan and Worden were crucial to their ultimate fates as murder victims because Ed selected them based on their vague resemblances to his mother, Augusta. In his muddled adaptation, Ormsby severely contradicts his pretension to fact by making the victims' counterparts decades younger. If Ezra wants to preserve the illusion of his mother's eternal existence, why would he kill women who are so far removed from her age that they couldn't hope to bear a resemblance to her? It's a choice that spoils Deranged's integrity with more of a generic slasher vibe.

More egregiously, Ormsby clearly doesn't have a lot of faith in the horror inherent to the real story because he weaves a plot development stolen directly from Psycho: Ed Gein may have exhumed nine corpses to decorate his home, but he had enough respect to leave his mother's grave alone. In Deranged, Ezra commits the same act as Norman Bates, stealing Amanda's body from her grave and carrying on one-way conversations with her as she sits stiffly in her bed. When Robert Bloch imagined that detail, it was grotesquely inspired; Ormsby is just lazily copycatting. The set design of the Cobb farmhouse is a suitably slovenly but overall weak imitation of that of the Sawyers' from Texas Chainsaw. Lanterns hang from the ceiling, providing the only source of light in an otherwise dingy house short on electricity. The decaying corpses of freshly buried women provide Ezra his only source of company, whether sitting together in a bedroom or gathered around the kitchen table for supper. A stuffed owl on the table recalls Bates' penchant for taxidermy. Trash lies strewn all over the floor. It's a house you wouldn't want to enter even if someone paid you, but it sits in the shadow of the far more inventively detailed buildings occupied by the altogether superior trio of Gein-inspired monstrosities.

What's a slasher film without some good old-fashioned slashing? Similar to Hitchcock and Hooper before them (and Demme long after), Gillen and Ormsby approach the violence in Deranged with a fairly high degree of tact and low supply of blood, especially concerning the deaths of Maureen and Sally. The execution of the former's, pardon the pun, execution is by far the most artistic. As Ezra lies on top of Maureen, he uncovers a gun and aims it at her. He puts a pillow over her face, aims the gun at the pillow, and just before he pulls the trigger, the filmmakers cut to a framed photograph of Mr. Selby. Accompanying the loud bang is no blood, implausible an absence as that is, but an abundance of feathers flying over the picture and around the room. For Sally's more prolonged murder, the first part of which transpires in the hardware store, Gillen and Ormsby film Orr from behind, so when Ezra fires his first shot at her head, she simply falls forward in slow motion, conveying the sadness of the ambush without showing any graphic details. After waking up in the bed of Ezra's truck, Sally jumps out and makes a run for it through the snowy forest. Now, what I would like to know is how in the hell did Sally manage to not only survive a bullet to the head, but retain enough strength and stamina to run away afterward? Of course, the shot does seem to have put a strain on her intellectual capacity, seeing as how she trips and takes a frustratingly long time to get back on her feet, considering a rifle-wielding maniac is hot on her trail. In an instance of the most unfortunate irony that would only happen in a horror movie, Sally ends up getting her foot caught in a bear trap recently set by her boyfriend and his father, who are out hunting yet predictably too far away to hear her screams. In a last-ditch effort to protect herself, she makes refreshingly smart use of a bush behind her, but ultimately it's for naught. With the sadistic grin of a hunter whose puny, defenseless prey is in the palm of his hand, Ezra drags a screaming, crying Sally out from the bushes and positions his rifle straight at her. Same as with Maureen's shooting, the filmmakers cut away to a wide shot of the forest at the moment of impact, when the sound of Sally Mae's last scream is replaced by a loud bang, followed by silence.

Neither of these kills can hold a hatchet to the murder of Mary, which is far and away the most suspenseful set piece concocted in this film's lean 82-minute runtime. Stalking Mary in his truck from outside her diner late at night after closing, Ezra punctures the tires to her car, an act she attributes to rambunctious kids. He offers to drive her to a tire repair store, which she reluctantly accepts. During the deeply uncomfortable drive, Ezra pulls a Ted Bundy, driving past the repair store in favor of allegedly driving to his house so he can give her spare tires for free. While waiting in the truck after Ezra disappears in his house, Mary wanders inside and calls out for him, receiving no response. As she makes her way cautiously down the dingy corridor, the filmmakers switch to a POV shot, her lantern peeking out from the side of the frame. Mary enters a bedroom and is horrified to find a skull on the floor. Backing away, she turns around and finds herself confronted with a congregation of deteriorated, skeletal corpses. Sitting among the motionless crowd is Ezra himself, disguised behind the mask of someone else's face, beneath the long, blond hair from a dead woman's scalp, and enveloped in a blanket concealing someone else's skinned torso. The fast-cut close-ups of Mary's petrified face, the corpses, and a costumed Ezra evoke the scene in Texas Chainsaw where Terri McMinn's Pam stumbles into the Sawyers' lair. Like Pam, once Mary overcomes the initial paralyzing shock, she screams her head off and makes a dart for the front door, running back into Ezra's truck, where he effortlessly incapacitates her.

Waking up a short while later, Mary finds herself locked in a closet clad only in her bra and underwear. Realizing the only option for survival is to play along, Mary allows Ez to tie her hands to the chair in which she's seated at the kitchen table, surrounded by Amanda and some other stuffed guests. At first, I was taken aback by Moore's calmness in this scene, but quickly realized she was using the facade of stillness to disarm her assailant and strengthen her chances of survival. It's a wise choice on the actress' part. What impressed me the most about this scene is its refreshing lack of predictability. For a while, I genuinely couldn't tell whether Mary was going to make it out of the Cobb house alive. Because she's based on a real-life murder victim, I figured most likely she wouldn't, but it's to the credit of the filmmakers' unhurried direction and Moore's composed performance that I wasn't confident one way or the other. (From the second Ezra lays eyes on Sally, she practically had "Victim #3" written across her forehead.) As Ez begins to feel Mary up, she earns his trust by showing no resistance and passively agreeing to be his bride, her only request that he untie her hands, reasoning that it's impolite to treat one's better half that way. Successfully preying on Ez's childlike credulity, Mary seizes the opportunity to smash a beer bottle on his head and stands up, but in typical slasher movie fashion, all the doors are locked. Her only defense is the corpses at her disposal, and it isn't until she tosses Amanda's that the full wrath of Ezra is unleashed. He corners Mary, armed with a most creative improvised weapon in hand: a human femur bone, which he uses to bludgeon her repeatedly over the head. In a jaw-dropping departure from the restraint exercised in the murder scenes of Maureen and Sally, Ormsby and Gillen leave little to the imagination here, cutting back and forth in dramatic slow motion between Ez thrusting the bone downward and blood dripping from the top of Mary's head down to her face.

By contrast, the ending is far too convenient. To spare the filmmakers some leeway, in the real story, shortly after Frank Worden discovered his mother missing from her hardware store, he was able to put the pieces together competently enough to have Gein in police custody before the end of the day. It wasn't an intricate case of "Who are our potential suspects?" once Ed was confirmed to have been in the store earlier that day and the last person Bernice saw. True to the simplicity of the genuine ending, after Harlon's son, Brad (Brian Smeagle), goes to the hardware store and finds Sally missing, along with droplets of blood and her glasses on the floor, he and his dad call in the sheriff (Robert McHeady). Brad realizes Ez was the last person in the store with Sally after he and his dad left to go hunting, so the trio take a drive to the Cobb homestead, and before they even get out of the car, Sally's nude body is hanging upside down in the barn in plain sight. In slow-mo, Harlon and the sheriff rush inside Ezra's home through the front door and encounter him sitting at the kitchen table, drenched in blood from head to toe and laughing maniacally. Freeze-framing on a close-up of Ezra's dementedly joyous face, Carlson's final line of narration informs us that a few days later, a mob of townsfolk, led by former friend Harlon, burned down the Cobb farm. (Weird piece of information to end the movie on. How about telling us what became of Ezra himself? We can infer he was arrested, but what was his sentence? Was he found legally insane and sentenced to a mental facility for the rest of his life like Ed, or prison? Death penalty, perhaps?)

Ormsby's script contains some minor but nagging plot holes that reek of an incomplete draft. Harlon and Jenny, disturbed by Ezra's bachelor lifestyle and lack of apparent interest in companionship at his age, convince him to ask Maureen out on a date. Following her murder, they never ask about her or what became of their first meeting. Furthermore, she isn't even reported on the news as missing or deceased. And she lived in an apartment; did none of her neighbors hear the gunshot and think to check on her? Likewise, after Ezra snatches his mother's corpse from the cemetery, no police investigation is conducted into her exhumation. Then there's also a drunk guy played by Jack Mather who appears in two scenes and contributes nothing of significance in either. His first scene takes place at the tavern, where he drunkenly brags to Ezra about how he would have sex with Mary if he were younger, and his second in the hardware store, where he makes a purchase while Brad mocks him behind his back.

The repulsive discovery of Ed Gein's killing spree -- and his methods of interior decoration -- has served as the foundation upon which some of the most memorable villains in cinematic horror have been constructed; regrettably, the passage of 50 years has not elevated Ezra Cobb to anywhere near the upper echelon where his fellow Gein-inspired brethren reside. If you're morbidly fascinated by the groundbreaking true-life horror story of the Butcher of Plainfield and craving a film that sheds a light on the black-as-soot underside of human nature, choose from any of the three infinitely superior -- and ironically far more gloriously deranged -- aforementioned options.

5.1/10

Comments

Post a Comment