The Silence of the Lambs (1991)

As of 2024, only three motion pictures in history have walked away with the "Big Five" (otherwise known as the "grand slam") awards at the Academy Awards. Those five major accomplishments pertain to Best Picture, Best Actor, Best Actress, Best Director, and Best Screenplay (Original or Adapted). The recipients of said achievement are It Happened One Night (1934), One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest (1975), and most stunningly of all, Jonathan Demme's 1991 psychological slasher masterpiece, The Silence of the Lambs. It's no secret the Academy holds a fairly undisguised bias against the horror genre, as evidenced by the myriad genre entries of the 21st century that have failed to garner either more than a meager technical nomination (A Quiet Place - Sound Editing, The Lighthouse - Cinematography) or any at all. The only film that received its fair share of nominations, including the only win of the century thus far, is Jordan Peele's groundbreaking social thriller, Get Out. And the only reason for that is likely due to its socially relevant subject matter: racism.

However, back in the 20th century, the Academy seemed more open-minded to embrace the fact that horror is a genre of film like any other, and given the right screenwriters, directors, and casts, they can be works of art in their own right, sometimes even more entertaining or impactful than the more "prestige" dramas and thrillers that seem to have a better shot at capturing the eyes of the voters. Never has this been more evident than with Demme's Silence of the Lambs, a chilling, tautly paced, masterfully acted, beautifully directed, emotionally enrapturing exploration of the contrast between the most benevolent side of human nature and the bleakest. If only one horror film in history could win Best Picture, not to mention four other major awards, I'm grateful it got to be this one.

Adapted from the 1988 novel of the same name by Thomas Harris, The Silence of the Lambs recounts the enthralling story of Clarice Starling (Jodie Foster), an FBI trainee at the FBI Academy in Quantico, Virginia assigned by her superior, Special Agent Jack Crawford (Scott Glenn) of the Behavioral Science Unit, to interview renowned psychiatrist-turned-cannibalistic serial killer Hannibal "The Cannibal" Lecter (Anthony Hopkins) to obtain a psychological profile on an unapprehended serial killer known only as "Buffalo Bill" (Ted Levine), who has abducted, murdered, and skinned five women. The only thing these women seem to have in common is they're overweight. None live within the same district, and at the scene of their capture lies one "grim, all too familiar calling card" - their shirts, sliced up at the back.

While initially hesitant, Clarice is professional and determined enough to accept Jack's "interesting errand," as her goal following graduation is to work for him in Behavioral Science. Before sending her off, Jack is careful to inform Clarice that her assignment is only to visit Lecter, ask him questions laid out specifically on a questionnaire, and report back to him. Oh, and be sure to never tell him anything personal. "Believe me, you don't want Hannibal Lecter inside your head," he assures her. "Just do your job, but never forget what he is!"

"And what is that?" Clarice asks. In one of the earliest examples of Craig McKay's brilliantly concise editing, the scene transitions to an establishing shot of the Baltimore State Hospital for the Criminally Insane. "Oh, he's a monster!" the disembodied voice of Dr. Frederick Chilton (Anthony Heald) proclaims. "A pure psychopath." Ted Tally does a phenomenal job laying the ground work for the type of villain Hannibal Lecter is, preparing us through the art of dialogue for our approaching meeting with the Devil himself in human form. Although based on the unhinged glee Dr. Chilton expresses in his warnings, it becomes clear this movie may contain villains of a more insidious nature. As Clarice stands in front of his desk, too uncomfortable to even sit down, Chilton makes a brazen, far-from-subtle pass at the young trainee: "We get a lot of detectives here, but I can't ever remember one as attractive." Foster plays this awkward moment perfectly, looking around the room, down at the floor, giving a slight smile of forced appreciation. You can feel her discomfort on a nearly palpable level. Heald, meanwhile, exudes a perverted menace, sporting a nightmarishly creepy grin to go along with his borderline-serial killer voice. "Will you be in Baltimore overnight?" he asks. "Because this can be quite a fun town if you have the right guide."

Clarice, the most intelligent, focused, self-contained protagonist you could ever dream of for a horror movie, quickly but respectfully turns the douchebag doctor down. "I'm sure this is a great town, Dr. Chilton, but my instructions are to talk to Dr. Lecter and report back this afternoon." With his ego deflated like a punctured balloon, Dr. Chilton abruptly stands up, switches to a more businesslike tone, and escorts Clarice to the bottom of the institution, presented as hell on earth courtesy of Tak Fujimoto's evocative red lighting.

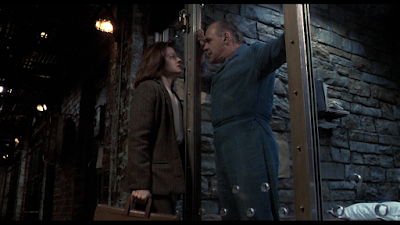

Walking down the hallway to her subject's cell, which happens to be at the very end, Fujimoto employs a nerve-wracking POV shot that puts us behind the eyes of Clarice Starling. Demme paces the scene slowly, allowing a sensation of unbearable tension to mount. McKay cuts back and forth between Foster making her way slowly down the hall, and the views ahead of her: the chair at the very end which has been placed for her, and the preceding cells containing violent inmates. The camera stares out at the chair, which seems a lifetime away, turns to the cells, then back to the chair. Everything Clarice sees, we see. It's an extraordinarily effective way of immersing us in her state of mounting anxiety. While two of the inmates sit in their cell, mumbling incoherently or saying nothing, one behaves like an untamed animal: "Multiple Miggs" (Stuart Rudin), who hisses to Clarice, "I can smell you cunt." Visibly uncomfortable but refusing to back down, Clarice proceeds to the final cell, and at the exact moment she is, we're introduced finally to the man who's been condemned as the personification of evil. But he's nothing we could have imagined in our heads. The former psychiatrist stands motionlessly, his arms resting against his body. His hair is slicked back, and he's dressed in a white short-sleeve shirt beneath a light blue jumpsuit. "Good morning," he says in a most gentlemanly tone.

This legendary moment marks the first of four in-person meetings between Clarice and Hannibal (their final exchange takes place over the phone), and the relationship they develop over a short period of time represents the core of The Silence of the Lambs. Initially, Dr. Lecter is welcoming of his young interviewer. He's apparently grateful to spend time with a woman for the first time in eight years, even if they are separated by a wall of bulletproof Perspex glass, and is willing to answer some questions that will help further her career in the FBI. However, he soon becomes insulted by her attempts to "dissect" the brilliant doctor with this "blunt little tool" and sends her away, humiliated and empty-handed. On her way out, Clarice is sexually assaulted by Miggs, which instantly galvanizes Lecter to reconsider his feelings about her. He implores her to seek out an old patient of his, "Miss Mofet," implying a connection between her and Buffalo Bill.

Using her intuition that Lecter's instruction to "look deep within yourself" was "too hokey" for him, the ingenious Clarice discovers an abandoned storage facility outside of downtown Baltimore named Your Self, and breaks inside to investigate. Locating the severed head of a man covered in makeup in a jar, Clarice figures out the name was an anagram for "miss the rest of me," meaning Lecter rented the garage. (How she came to that conclusion is beyond my comprehension, but man, do I admire her keen intellect!)

Returning to his cell, Clarice is informed the victim was a patient of Lecter's, a "garden-variety manic depressant" whose murder was a "fledgling killer's first attempt at transformation." Lecter makes Clarice a deal: he will offer a psychological profile on Buffalo Bill and help her capture him, and in return he wants to be transferred away from Dr. Chilton, whom he views as his nemesis. The stakes are raised once Buffalo Bill abducts his sixth victim, Catherine Martin (Brooke Smith), the daughter of Republican U.S. Senator Ruth Martin (Diane Baker). Unfortunately for Clarice, Hannibal is a man who prefers to drop the vaguest of clues piecemeal. Will she be able to capture Buffalo Bill in time to rescue Catherine?

For their performances, Jodie Foster and Anthony Hopkins were each awarded the Oscar for Best Actress and Actor respectively, and not only did they earn it, but it wouldn't be a stretch to say they have delivered the two greatest performances in the history of horror bar none. Not only that, but Clarice Starling and Hannibal Lecter are the most three-dimensional characters of their respective categories (Clarice/protagonist, Hannibal/antagonist). From the opening frame, Foster demonstrates Clarice's tenacity and endurance: climbing a hill by rope, sprinting through the woods, climbing over a cargo net, jumping over logs. The sweat on her chest speaks volumes of how tough and driven this woman is, without her uttering a single word. Her long-term goal is explicitly stated in a dialogue between her and Jack: she wants to work for him in the Behavioral Science Unit. Clarice is confident enough to hold her own against both condescending doctors: the one who flirts with her and considers it "clever" that Crawford sent a woman to interview a serial killer, and the one who viciously dissects her down to her West Virginia, "poor white trash" origin. However, she's psychologically burdened by two traumatizing events from her childhood, both of which are unveiled in the engrossing dialogue between her and Hannibal. Responding to Hannibal's quid pro quo - "I tell you things, you tell me things" - she divulges that her worst memory is the death of her policeman father, who was shot by two burglars in the process of capturing them at a drug store. She shared a close relationship with him because her mother died when she was very young, so he became "the whole world" to her. Following his death, she went to live with her mother's cousin and her husband on a sheep-and-horses ranch in Montana. Though never stated explicitly, it can be assumed that Clarice's desire to become an FBI agent is fueled by her late father's profession. He spent his life trying to catch criminals, and Clarice wants to make him proud by following in his footsteps. The beauty of Ted Tally's dialogue is it offers enough information to reveal the histories and personalities of his characters organically without spoon-feeding the audience unnecessary exposition. He trusts us to reach certain conclusions on our own.

During their third and most pivotal conversation, Hannibal extracts the driving force behind Clarice's unceasing determination to capture Buffalo Bill and save Catherine. One morning, she was awakened by the terrible screaming of spring lambs on the ranch and opened the gate to their pen. When she realized they were too frightened and disoriented to move, she heroically picked one up and ran away, only to be picked up herself by a cop car and returned to the ranch, where the lamb was slaughtered with the rest of them. Angered by Clarice's action, her cousin's husband sent her to an orphanage. Hannibal accurately deduces that Clarice still suffers from nightmares of the lambs screaming, and believes that if she can save Catherine, the nightmares will end and the lambs will become silent. Hence, the "silence of the lambs," which is not only one of the most memorable horror movie titles in and of itself, but once the psychological meaning behind it becomes apparent, it is arguably the greatest. For Clarice, saving Catherine isn't just a matter of her doing her job and advancing her career: it's a matter of personal redemption. She couldn't save that one poor little lamb from being slaughtered, but she'll do everything in her power to save an innocent young woman from suffering the same fate.

The Silence of the Lambs is Clarice's story. While her assignment is to plunge into the twisted mind of a serial killer, this is first and foremost a character study of her: what motivates her, what terrifies her, what goals she's aiming to achieve and why. She receives the most character development, and as portrayed by Jodie Foster, she is a thoroughly compelling character. Almost every scene is presented from her point of view, and we're beside her and rooting for her throughout the entire harrowing experience. It's practically insane to consider that, when casting was underway, Foster was not Demme's first choice for the role. In fact, she wasn't even his second. And guess what? She wasn't his third. No, Demme's preferred pick was Michelle Pfeiffer, who turned down the role because of the violent subject matter, a decision she likely regrets today. Next on the list was Meg Ryan, who likewise rejected the offer due to the gruesome themes. When the studio expressed doubt that Laura Dern would be a bankable choice, Demme finally awarded the role to Foster, whose passion for Clarice is apparent in every scene in which she appears.

While Hopkins submits the showier performance as the flamboyant doctor with a thirst for human blood, Foster delivers the more grounded performance. She serves as our guide through this terrifying journey into the depraved underbelly of human nature. We experience every unsettling sensation, every chill that runs down our spine, every tear that wells in our eye, alongside her. As a woman fighting every day to succeed in a profession dominated primarily by men, Foster brings Clarice to life with an assured exterior that masks deep internal wounds. In the aforementioned scene with Chilton, Foster makes her unease palpable, doing her best to politely thwart his advances without losing her composure. Thanks to Tally's sharp writing, she is permitted to let loose with a couple witty rejoinders. When she asks to speak with Hannibal alone, Chilton suggests she might've mentioned that in his office and saved him the time of escorting her. "Yes, but then I would've missed the pleasure of your company." This is a woman who knows how to handle herself around creepy, intimidating older men.

During her first interaction with Hopkins, Foster suppresses her discomfort with a nervous chuckle. As he begins belittling her, her mouth quivers, her eyes reflecting profound humiliation. She's struggling mightily for inner strength, and once he's finished, she snaps right back at him, challenging him to redirect that "high-powered perception" at himself. In a genre that's come a long way from the offensive damsel-in-distress stereotype that prevailed in vintage horror, Clarice Starling reigns supreme. Foster makes Clarice tough-minded and inflexible, ensuring that she never seems out of place in her testosterone-heavy environment, but isn't afraid to display the vulnerability and inner pain that makes her relatable and human. When it comes to expressing pure, naked fear, she is magnificent. Take the unplanned reaction she gives when Hopkins surprises her with an ad-libbed slurp. Her eyes widen with terror. She can't move a muscle. It's the most honest response that perfectly reflects the tension felt by the audience. Foster conveys a quiet assertiveness, as evinced at the funeral home when she orders a group of policemen to leave the room. She expresses appreciation for their sensitivity toward the victim's family, but insists she and her team can take over from here. As they stand there, giving her condescending looks ("Who the hell does this woman think she's talking to?"), she reasserts her authority in a manner that doesn't offend or express offense: "Go on, now!" she says in a level tone. Clarice is someone who doesn't demand respect, so much as she commands it.

One of the ways Clarice proves her belonging in the FBI is the way she handles the inherent sexism in her workplace. Much like Clarice herself, Demme and Tally neither overstate nor understate her femininity. On her way to Crawford's office in the opening minutes, Clarice steps inside an elevator filled with men, all of whom tower over her. Foster doesn't show discomfort or annoyance at their air of superiority. She clasps her hands together and stares up at the ceiling, not even acknowledging their presence. Later, when she's running through the woods with her friend, Ardelia (Kasi Lemmons), a group of men run past them and turn their heads, snickering. Are they just attracted to these two badass women earning their place in a man's field? Or are they privately mocking them for even trying to gain entrance? Much of this subtext is left open to interpretation. At one point, Crawford uses Clarice's gender to get rid of the sheriff and some other men, insisting he'd rather discuss the details of a naked woman's murder away from her "delicate" ears. The feelings of betrayal and embarrassment flash across Foster's face, but she is a master at internalizing them. Fujimoto then places us in Clarice's subjectivity, showing the uniformed men in the room glaring at her, misogyny emanating from their eyes. But is this how these men are actually looking at her, or is this just how she imagines them looking at her?In a car ride later that evening, Crawford acknowledges Clarice's hurt at his strategy and insists he didn't mean anything by it. Her response and the levelheaded manner in which Foster delivers it is pure genius. "It matters, Mr. Crawford. Cops look at you to see how to act. It matters." No screaming, no eye-rolling. No cold shoulder. Just three words that respectfully convey her righteous resentment. This is how she proves that she belongs in the FBI.

On the opposite end of the spectrum is Hannibal Lecter. While Clarice embodies the most benevolent and hardworking of humanity, Hannibal embodies the near-complete absence of any. Without a backstory to provide any context, Lecter is presented as the vessel into which all the world's evil can be contained. Upon first glance, though, he comes across as a normal, low-energy human being, if a lot smarter than average. Before we are even introduced to him, Tally implants in our minds a faithful depiction of the malice lurking beneath the placid exterior. There's never any doubt as to his guilt; he openly brags about his crimes without a hint of remorse. Hannibal is far from your typical cinematic slasher. Not dissimilar to Clarice, he's highly intelligent, resourceful, cunning when he needs to be, and driven by a personal objective. It's no wonder the two of them develop such an understanding with each other: they're two sides of the same coin, and that's what makes them the most fascinating pair. Clarice uses her intelligence for good -- to save Catherine and put an end to Buffalo Bill's killing spree -- and Hannibal for evil -- to escape confinement and kill more people. Point is, they each have their own desire that fuels their behavior. When Hannibal murders his two guards, it isn't merely for the joy of killing two authority figures who were foolish enough to think they could contain him: it's motivated primarily by his desire to be free from prison, and most importantly, Dr. Chilton. In place of a view of the outside world, Hannibal utilizes his talent as an artist to sketch images based on mere memory.

With approximately sixteen minutes of screen time, Anthony Hopkins dominates every second of them, and in the process creates the most multifaceted villain in horror. Despite one unforgettable sequence that finds the doctor strapped to a hand-truck in an orange jumpsuit, a white straitjacket, and a muzzle (in fact an upside-down goalie mask), Hopkins spends most of the movie unmasked and inside a cell or cage. Despite his limited mobility and physically slender frame, Hopkins utilizes his overwhelming presence and soothing British voice to flesh out a character of fascinating contradictions. When speaking to women, Lecter alternates between chivalry and sadism. During his face-to-face meeting with Senator Martin, he begins by taunting her over the possibility her daughter is currently being butchered -- "Amputate a man's leg and he can still feel it tickling. Tell me, Mom, when your little girl is on the slab, where will it tickle you?" -- before offering a physical description and potential address of the abductor. He even compliments her suit before she goes.

The artistry behind Hopkins' sensational, larger-than-life, scene-stealing performance is that he manages to combine these contrasting traits into one credible human being, as opposed to feeling like a jumble of contradictions mashed awkwardly together. A sophisticated, articulate creature whose roots in psychiatry account for his conversational personality, Lecter isn't above vulgarity, asking Clarice if she thinks Crawford has fantasies about "fucking" her. His methods of murder are inhumane and visceral, biting people's faces, eating their tongues, skinning them alive, bludgeoning them. But unlike his fellow slasher brethren, Hannibal possesses the unique ability to get inside people's heads and compel them to commit atrocities against themselves. Seeking vengeance on behalf of Clarice, he whispers to Miggs from his cell and inexplicably inspires him to chew off and swallow his own tongue. Without even leaving his cell or using weapons (apart from his own brilliant mind), Hannibal is capable of ripping someone to shreds. If he were a real-life serial killer, he would possibly surpass the evil genius of Charles Manson, and almost certainly earn his warmest approval.

Most interestingly, in spite of his clear disregard for the lives of most human beings, Hannibal develops a sense of protectiveness and appreciation for Clarice. His heart is otherwise cold and black, and yet when it comes to her, a remnant of humanity seems to surface. He admires her drive, sympathizes with her grief over her father's death (he isn't moved to tears, but when he closes his eyes, you can feel it), and takes pleasure in learning personal details of her life. He doesn't do anything malicious with the information, he simply wants to know, and when she shares her most traumatic memory, he thanks her. Tally and Hopkins are careful not to reveal a romantic attraction between the pair. Like other aspects of a magically nuanced screenplay, it's left ambiguous. Hannibal does seem to harbor a sexual desire for Clarice, the only woman he's not only seen in eight years, but who matches his intellect and boldness. To him, she's a reminder of the good that still exists, and for that, he decides to help her get where she wants to be. So he drops tidbits of information to guide her in the right direction, such as anagrams for her to crack, but he never spells out the answers, trusting in her genius to find them on her own. For Clarice, on the other hand, Hannibal is little more than a task, a ladder toward her goal. As instructed, she never forgets what he is. In an effort to motivate him to reveal information on Buffalo Bill, Clarice presents him with a phony offer on Crawford's behalf: if he helps them find Bill in time to save Catherine, Senator Martin will have him transferred to an island where, for one week of the year, he may walk on a beach and swim in the ocean for an hour. When Hannibal realizes he'd been deceived, his respect for Clarice remains, if not increases. She may not be a murderer, but she isn't above resorting to lying and manipulating to attain her goals. While a physical attraction may be one-sided, a degree of respect is mutual, as Clarice only addresses the cannibalistic psychopath as "Dr. Lecter" from their first conversation to their last.

Hopkins counteracts Hannibal's callous nature with a stillness that radiates serenity. He's often courteous and soft-spoken, which makes his moments of physical and verbal savagery all the more jarring and unexpected. His tonal delivery is measured and confident, articulating each word with precision. He stares with unblinking, penetrating eyes, and his lips part in a devilish smile when he knows he's dissected his subject accurately. Hopkins' physicality is so mesmerizing as to never need more than his God-given face to instill pure, blood-freezing, heart-stopping terror. In addition to his variegated facial expressions, he does stellar work with his voice, sometimes descending into a haunting whisper. When he bludgeons Lieutenant Boyle (Charles Napier) over the head with his own Billy club, Hopkins' movements are balletic and graceful, like he's conducting an orchestra. He makes killing an art form. Afterward, he waves his hands peacefully over a radio playing serene music, his head facing up with his eyes closed. He's got all the time in the world -- even as an injured Sergeant Pembry (Alex Coleman) crawls away. Hopkins plays Hannibal as a wolf in sheep's clothing, inhabiting the skin of a mortal man and wearing the mask of convincing civility, without suppressing the despicable, unsympathetic creature lurking beneath the surface.

Because the story is told from Clarice's perspective, and her visitations with Lecter are purely for business, and Lecter's demand is for Clarice to expose her interior self to him, it makes sense we never learn about his backstory. What drove Hannibal to forfeit his humanity and become the literal bloodthirsty monster we know him to be? Tally smartly renders that question irrelevant. With Hopkins in the role, Hannibal is a compelling enough villain as is, and his backstory wouldn't figure into the narrative in a way that would make sense. Clarice is the character we're meant to connect with on an intimate level. It's her life Hannibal is interested in learning about. Clarice's questions for him pertain only to ascertaining the identity of Buffalo Bill, so it wouldn't be logical for Hannibal to start disclosing his own life story. He not only doesn't feel remorse for the people he's already killed, but he desires freedom so he can kill more people. And he doesn't want sympathy, nor is he deserving of it, no matter how tragic is upbringing likely was. Hopkins understands his villain enough to have fun with his love for evil, to flaunt his shameless dearth of remorse like a badge of honor. And yet, while we're not exactly "happy" for Hannibal once he achieves freedom because, yes, he's a remorseless killer, on some indiscernible level we share in his exhilaration because he's so unabashedly reprehensible. And also he concocts such an elaborate plan that you can't help but admire his tenacity. How many serial killers have you heard of who achieved their freedom by utilizing a pen cap?

The pinnacle of Clarice and Hannibal's steadily developing relationship is reached when she visits him in a Tennessee jailhouse, where he's (fittingly enough) imprisoned inside an animal-like cage. Clarice urges him to continue helping her find her target, and despite her earlier deception, he agrees on the condition she finishes telling her story on the ranch. This is the final onscreen collaboration between the pair, and it's executed into the most dramatically powerful and emotionally wrenching sequence of the movie. In the script, Tally wrote a flashback that would visualize Clarice's traumatic experience with the lambs. Demme made the economical choice to eschew the flashback and rely on three basic ingredients: camerawork, editing, and the acting ability of his two dynamite headliners. As Foster recounts her heart-rending childhood tale, Fujimoto zooms in for close-ups of both actors, contrasting Hopkins' steady, unblinking gaze with Foster's wavering, mournful one. McKay uses shot/reverse shots to give them space to say their lines: Hopkins' penetrating questions and Foster's agonizing answers. Both faces fill the screen, immersing us in Clarice's psychological torment and Hannibal's intense fascination. Foster is at the top of her game in this scene. Whereas Hopkins' eyes are all but glued to her, she fails to make consistent eye contact, her eyes often roaming to the side as she relives this harrowing memory in her mind. Every answer is being dragged from her like teeth, and her voice descends into a strained whisper. Tears of regret well in her eyes. When she expresses her naive thought process at the time ("I thought if I could save just one..."), she flashes a momentary, wistful smile. We can almost see the flashback unfolding behind Clarice's eyes, so a literal one wouldn't have been necessary.

While the starring performances of Hopkins and Foster will always sit at the forefront of The Silence of the Lambs, the acting is outstanding across the board. In addition to the five Oscars it took home in 1992, it was also nominated for two more: Best Editing and Sound Mixing. For my money, it deserved two more nominations even more: Best Supporting Actor for Ted Levine and Supporting Actress for Brooke Smith, who perform the leading roles of Lambs' subplot. Buffalo Bill, whose real name is Jame Gumb, and Catherine Martin could be seen as secondary versions of Hannibal and Clarice, but that would be doing both characters (and actors) a major disservice. These are two of the most richly developed supporting characters I've ever encountered in a horror story, and they deserve better than to be relegated to the shadows of their primary counterparts.

He may not quite match Hannibal in unbreakable composure or psychological weaponry, but Buffalo Bill is nonetheless a terrifying villain. With echoes of real-life misogynistic serial killer Ted Bundy, he preys on the kindness of unsuspecting young women. When Catherine returns to her apartment, her cat waiting for her at the window, Buffalo Bill, wearing a cast on his arm, gains her sympathy by struggling to lift a couch into his van. He asks her to get inside the van so they can push it all the way in. Once inside, he knocks her unconscious after accurately deducing her size, and drives off. The parallel to Bundy ends there, as Billy's modus operandi is even more cruel. While Bundy would beat his victims with a crowbar and strangle them, Bill imprisons his women at the bottom of a well in his basement, starves them so he can loosen their skin, then shoots them, disposing of their bodies in various rivers. His ultimate goal is to craft a woman's suit out of his victims' skin.

The wonderful thing about the dialogue in The Silence of the Lambs is that every conversation serves a purpose. It reveals layers about the characters and moves the story forward just as dialogue should. Much of the script is composed of the exchanges between Hannibal and Clarice, and they're beautifully written and invariably enthralling. On their second meeting, Hannibal offers a revealing observation about Buffalo Bill: he's a man who loathes his identity so much that he falsely believes himself to be a transsexual. Not only does this enlighten us as to the killer's psychology, but it further demonstrates Hannibal's perception. Like the bloodthirsty doctor, Bill's backstory isn't delved into, but it's inferred he wasn't born a criminal, rather turned into one "through years of systematic abuse." Tally is wise to note the lack of correlation in literature between transsexualism and violence, making it clear Bill wants to transform into a woman not because he was legitimately born into the wrong body, but because he desperately desires to be anything other than what he already is. Whatever happened to Bill in his childhood has deprived him of all compassion and empathy for human life. He deliberately refers to his victims as "it," thereby dehumanizing them into mere objects to be torn up. In an unconventional twist, however, he does possess one shred of humanity: love for his dog. Most serial killers begin their career by murdering animals; for this killer, his dog is the only living thing he's capable of loving and nurturing. Now, how many horror movies provide two fully dimensional, terrifying monsters for the price of one?

Ted Levine brings this human monster to life in an extraordinarily layered performance, his lean yet muscular physique contrasting frighteningly with effeminate mannerisms that display the internal conflict within. He speaks in a sonorous, creepy voice that gets even more unsettling when he switches to a baby tone for his dog, Precious. Hate and darkness emanate from his intense eyes, as shown when he's at work on his sewing machine. As Catherine pleads with him to set her free from the well, Levine uses an effeminate voice to calmly command her to rub lotion on her body and put the bottle in a basket. She begs to be reunited with her mother, and growing frustrated by her disobedience, he switches to a deeper, more authoritative tone: "Put the fucking lotion in the basket!" Watching her scream at the sight of broken fingernails on the wall, Levine begins to mimic her, letting out a mocking series of screams while tugging on his shirt. Hopkins may offer the more insidious portrayal of evil, using a chivalrous demeanor and soothing voice to disguise his psychotic nature, but Levine is more terrifying in the traditional sense of a nightmare.

Brooke Smith is afforded the opportunity to do something clever with her archetypical damsel-in-distress role. When we first meet Catherine Martin, she's in her car singing cheerfully to Tom Petty's "American Girl" on the radio. Before she can make it in her apartment to feed her expectant cat, her inherent kindness gets her enslaved by the deceptive force of evil that is Buffalo Bill. Spending the remainder of her screen time largely trapped in a well, Smith is heartbreakingly raw and sympathetic, pleading with her abductor to spare her life. At first she tries to reason with him, offering money from her wealthy family in exchange for her safety. Then she makes an attempt to appeal to his virtually nonexistent emotions, reverting to a childlike plea to see her mother. Smith is an incredible screamer as well, giving an authentically hysterical reaction to the realization of what's in store for her.

Catherine isn't content to remain a victim, however. Tally imbues her with an unexpected resourcefulness and inner ferocity that Smith portrays with equally brilliant conviction. Realizing her captor can't be reasoned with, Catherine devises a plan to turn the tables on him. Using the materials at her disposal -- a bucket and scraps of food -- she lures Precious down into the well, having observed she's the one thing her attacker cares about, and deploys her as bait. In turn, Buffalo Bill undergoes character development of his own, displaying a hitherto-unknown vulnerability and desperation that engender sympathy. Until this point, he's been in complete control. Now he's the one pleading, almost in tears, for the safety and return of his beloved dog. Levine is phenomenal in this scene, conveying a genuine concern for his pet's welfare that's surprisingly heart-wrenching in its relatability. He unearths the fragile human being beneath the monster, and his guttural delivery of the reply, "You don't know what pain is!" implies a lifetime of severe abuse in one sentence better than a monologue of exposition could.

As for the commanding Smith, I wouldn't mind seeing a sequel revolving around her character. I would love to see what's become of Catherine following her life-changing ordeal. With her blend of vulnerability and strength, she's like a miniature Clarice. I could envision a future in which she joins the FBI herself, using her trauma as fuel to rescue people in a similar predicament to her own and put a stop to the criminals. That would've made for a much better approach than the one taken by Ridley Scott's 2001 follow-up, Hannibal.

While this exchange is transpiring, McKay employs his most impressive editing trick of the movie, deceptively intercutting exterior shots of Crawford and an FBI Hostage Rescue Team surrounding the outside of the killer's home with interior shots of Buffalo Bill in his basement. We instinctively share in the FBI's assumption that they've located their target, and the most ingenious move is a match-on-action cut where a man rings the doorbell on the outside, followed by a shot of a bell ringing on the inside. When the killer answers the door, it's Clarice, without any protection. Jack and the HRT men storm the other home, crashing through the windows with their guns extended, only to find it abandoned. Cleverly, this nifty editing is blended with masterfully written and acted character development for both Buffalo Bill and Catherine, making the sequence more than a technical exercise in manipulating the audience.The aforementioned address mix-up may be responsible for Lambs' editing nomination, but truthfully, Craig McKay does phenomenal work throughout the entire film. With a demanding runtime of 118 minutes, McKay makes every one of them count. There isn't a wasted shot or exchange to be found. His editing is blissfully brisk, making the near-two hours breeze by without an ounce of excess fat. Cases in point: while Clarice is talking to Crawford on the phone about the Your Self parking garage, McKay uses an L-cut to transition to an establishing shot of the setting before she finishes her sentence. After Clarice uncovers the severed head of Benjamin Raspail, filmed in detailed close-up, McKay hard cuts to her arrival at Hannibal's institution, skipping over her escape from the garage. And yet the pacing is never rushed. Demme exhibits the patience to endear us to his characters, to allow a feeling of unease to set in when we know something awful is coming. In the pitch-black parking garage, illuminated only by a flashlight, Clarice wanders slowly and cautiously. Demme isn't in a rush to get to the money shot. That way, when it's provided, it's earned. When Hannibal is getting ready to execute his escape, Fujimoto zeroes in on his face, calm, patient, at ease. We get a close-up of Hopkins' hands, cuffed behind his back, one hand sliding a pen cap into the lock as the sergeants fail to take notice.

Demme allows us access into Clarice's mind in part through flashbacks to her childhood, and McKay transitions seamlessly between the past and present. For example, as Clarice exits the Baltimore State Hospital and heads to her car, McKay cuts to a younger version of her, played by Masha Skorobogatov, greeting her father as he gets out of his car. She runs into his arms and asks if he caught any bad guys. When we cut back to present-day Clarice, she's sobbing at her car, emphasizing the emotional component of the story. Later at the funeral home, Clarice pokes her head through the door to see the attendants gathered in the chapel. She moves forward, almost in a dreamlike state, and as the camera zooms toward the casket, McKay cuts back to a 10-year-old Clarice approaching her father at his funeral. It's difficult to determine at which point the present footage ends and the flashback begins.

Diane Baker is only in two scenes, but she makes the most of them, delivering a moving portrait of a mother desperate to get her little girl back in peace. In her first scene, her senator makes a dramatic plea to Buffalo Bill on TV, smartly repeating Catherine's name in the hope it will humanize her in her captor's eyes (to no avail). Baker's voice is composed but brittle, her eyes red with tears. She's doing everything in her power to keep from breaking to pieces, and she succeeds. When she has her face-to-face with Hopkins, Baker holds her own against the Shakespearean master, her face nothing more than a mask of strength cracking bit by bit as Hannibal heartlessly toys with her like a cat chewing on a mouse.

Scott Glenn is a pillar of strength for Foster. As Jack Crawford, he serves as her connection to the bright side of mankind. He's protective over Clarice like a father figure, confident in her ability to handle a man as dangerously manipulative as Lecter, but instilling in her a caution to steer clear of his tricks. When he realizes Clarice is in the house with Buffalo Bill, the camera zooms in on his face, suddenly terrified for her safety. Following her triumph, Jack rushes to her and wraps an arm around her shoulder, waving away the reporters. It's clear she means more to him than a student. At her graduation, he claps for her as she walks on stage to accept her certificate. Before leaving, he extends his hand in respect, warmly stating her father would've been proud.

In a contrary role, Anthony Heald is clearly having a blast, mugging it up as the smarmy, chauvinistic Frederick Chilton. He's the general administrator of Baltimore State Hospital, although he behaves almost as if he truly belongs downstairs with his own patients. For his introduction, Heald, like all of his costars, is filmed in close-up as he converses with Foster, all the better to capture his insanely creepy grin. After secretly recording the exchanges between Clarice and Hannibal, he antagonizes his patient by revealing the transfer deal as fraudulent. He lies in Hannibal's bed chewing on a pen cap, cocky and withering. At one point he struts down the hallway of a courthouse wearing a flamboyant fur coat, same bombastic grin on his face. Chilton may not technically qualify as a villain, but when his fate is hinted at in the final seconds, it's impossible not to feel grateful.

The bread and butter of a slasher film is, of course, the slashing. When we think of typical examples of the subgenre, graphic eviscerations and beheadings come to mind as quickly as they're splattered across the screen. The entire appeal of them is turning carnage into candy, something for audiences to cringe at, shield their eyes from, or cheer for. It's a vicarious rollercoaster ride. What distinguishes The Silence of the Lambs -- and fools people into thinking it isn't "really" a horror movie -- is its restrained presentation of violence. There are only two instances of onscreen brutality, and even those are handled with tact. The first is when Buffalo Bill punches Catherine. Because she's in the van, we only see Levine. He swings his arm, a violent thud is heard, and an unconscious Smith is lying face-down. When Hannibal lunges at Sgt. Pembry with his mouth open, his teeth clenching down on his nose, we only see the victim's widened eyes. As he drops to the floor, blood dots his face. The only murder depicted is of Hannibal bludgeoning Sgt. Boyle. Demme relies more on ratcheting a sense of impending doom. As Boyle frantically tries to unlock his handcuff, Hannibal slowly approaches him with an upraised Billy club. Boyle lets out a defeated scream, and Hopkins brings the weapon down. Blood sprays on his face, a horrible thud is heard upon each whack. When Boyle is shown, lying lifelessly on the floor, his arm is covering his face as blood trickles down beside him.

One of Lecter's most vicious attacks from a decade ago is left to the imagination in the most inventive way. Before Dr. Chilton takes Clarice to meet Hannibal for the first time, he recounts in gleefully graphic detail an incident where he complained of chest pains. When a nurse bent over him, Hannibal ate her face off. In case she doesn't take his warning seriously, Chilton gifts her a picture of the nurse after the attack. Fujimoto captures Foster's reaction in a low-angle close-up shot. The horror in her expressive eyes, combined with Chilton's final bone-chilling line ("His pulse never got above 85... even when he ate her tongue."), paints a more gruesome image than an explicit flashback would.

Demme mostly uses graphic imagery to convey the monstrosities of Buffalo Bill. Crime scene photos of his victims -- lying on their stomachs with their backs skinned -- are taped to the wall in Crawford's office. One woman from West Virginia, whose body has been dredged up from a river, is displayed on a table at the funeral home for an autopsy, but Demme and Fujimoto focus more on the repulsed facial reactions of her viewers, turning their heads, closing their eyes. Rather than make a spectacle out of the lifeless woman, Demme and Fujimoto provide glimpses of her dirtied body and limbs: leaves stuck to her arms and legs, her hands purple, fingernails broken with dirt underneath. The side of her face is briefly shown, covered in dirt. By the end of the scene, we're treated to a full body shot, featuring two diamond-shaped carvings in her back.

Also unlike most entries of its ilk, The Silence of the Lambs commemorates its victims. It's common for slasher victims to register strictly as body count, human props deployed to show up, maybe say a few lines, and receive a violent kill. And while we don't learn about the lives of Buffalo Bill's five victims, Tally and Demme treat them as more than graphic photographs. After Clarice realizes, with help from Ardelia, that Buffalo Bill knew his first victim, Frederica Bimmel, she travels to her hometown and speaks with two of the people who knew her most: her father and friend. Neither actor is onscreen for long, but Demme and Fujimoto afford them the space (i.e. the entire frame) to quietly convey their grief. That's the beauty of Fujimoto's camerawork: under Demme's empathetic direction, he films the actors frequently in close-up to highlight their emotions, and he holds on it. It isn't an empty visual style, it creates a beautiful bond between the audience and the characters. The screen separating us is no more hindering than the glass wall or cage bars that separate Clarice and Hannibal; their connection is electric and undeniable, no matter their physical restraints.

While faces are the primary focus and purpose of the close-ups, Demme also uses them to highlight significant objects. In the scene where Chilton is taunting Hannibal about his slim prospects of ever leaving his cell, Fujimoto and McKay use shot/reverse shots to show Hannibal staring intently at Chilton's pen. The camera cuts back and forth between the seemingly unimportant object and Hopkins' fixation on it, both subjects zoomed in for close-ups. We can see the mad doctor cooking up a whole plan in his mind, all thanks to the inspiration of one miniscule everyday prop.

One more Oscar The Silence of the Lambs should've been nominated for is Best Original Score for Howard Shore. Before the first frame is even presented, our ears are treated to my personal favorite theme in all of horror. It begins softly and slowly, a peaceful, mournful melody that would be at home in a drama. Then once Clarice picks up speed on her run through the Oregon woods, determination and grit sweating through her pores, the music grows in intensity. It's a riveting accompaniment to the character's mindset. Like the best movie scores, Shore's never threatens to overwhelm the scenes in which it's played. Rather, it adds to the intensity of certain scenes while emphasizing the poignancy of others. It's mesmerizing, gorgeous, and emotionally impactful.

The climactic confrontation between Clarice and Buffalo Bill is a master class in pacing, lighting, acting, production design, and perspective. Buffalo Bill escapes to his dungeon-like basement, armed with a gun, and Clarice pursues him. Gripping her gun tightly in her hands, she slowly makes her way through a seemingly endless maze of closed doors and loose moths. It's dank, the walls are rotted, mannequins stand by ominously, photos of the five victims and a map showing the locations of the rivers in which their bodies were dumped are taped to the walls like perverted trophies. This basement is an entire world, ripped straight out of your worst nightmare. Demme's direction is appropriately slow to instill excruciating, hand-wringing tension, submerging us in Clarice's fear and disorientation, without dragging on a second longer than it needs to. He keeps us attached to her throughout the entire journey, allowing us to identify with her terror. The killer is nowhere in sight, so we're just as in the dark as she is. He could be behind any door, and there's so many she's forced to open. Fujimoto aims the camera at the inside of one door, and as it slowly opens, we instinctively fear he'll be standing behind Clarice. But he isn't. It's the most nerve-racking climax of any horror movie. In a bathtub lies the decaying corpse of a woman, perhaps the old homeowner.

Then the lights go out, and we're plunged into total darkness. When a light turns on, though, we're no longer in Clarice's perspective. Demme transfers us behind the eyes of Buffalo Bill, staring at his blinded prey through night-vision goggles. The screen is now bathed in lime green, and Clarice is the only one not afforded some light. Foster pants with disoriented terror, one hand quivers as it grips the gun, the other hand reaches out and clenches for something to grab onto. Her eyes are unnaturally wide, she keeps her back against the wall, and stumbles. It truly feels like watching someone struggle to find their way in the dark. We're now in the position of power alongside Levine, and in a brazen display of cockiness and sadism, he reaches his hand out toward her face, relishing the control he has over her. He could kill Clarice any second he chooses, but he's going to make her suffer in the dark just a little more. Demme makes the smart decision to let the scene play out in silence. The only sound we hear is of Foster's heavy breathing. Then the dramatic music commences softly. Having had enough fun, Bill extends his gun and cocks it. With an acute sense of hearing, Clarice automatically spins around and fires multiple shots into her target's chest. Because she's as smart as horror protagonists come, Clarice doesn't fire one shot, but multiple. She demonstrates a highly developed sense of self-preservation, as when Gumb is lying on his back, spitting up his own blood, she refuses to take any chances. She instinctively reloads her gun and aims it at the dying man. This is a woman who's learned from her training, and without a doubt belongs in the FBI.

In the end, this is an uplifting story of triumph for Clarice Starling. She not only secured her spot in a largely male-dominated profession and showed every man who looked down on her that she has what it takes, but she saved the life of an innocent young woman and returned her in the arms of her mother (along with a new pet). She took on a psychotic killer in his own domain, with no help or backup from any male agent or officer. She didn't just read him his rights and slap on a pair of handcuffs. She put a permanent stop to his evil and helped make the world a better place. Clarice is a hero. Watching her walk across the stage at her graduation ceremony to accept her diploma, we feel the same pride for her that Ardelia expresses. It's a deeply inspiring ending, but Tally isn't ready to let us off the hook entirely. He's got one more surprise in store: a phone call. When Clarice answers, it's Hannibal, asking if "the lambs have stopped screaming." He's stolen the clothes of a tourist he killed, a clean white suit, a wig, pair of shades, and fedora. In a film loaded with iconic lines and dialogue, Tally has saved the best for last. As he watches his nemesis step off a plane, Hannibal tells Clarice, "I do wish we could chat longer, but... I'm having an old friend for dinner." It's the most clever double entendre I've ever heard, and probably the greatest closing line in the history of horror.

As Hannibal trails behind Chilton, surrounded by an abundance of tourists, Fujimoto tracks away from him before slowly ascending into the air in a crane shot, observing Hannibal as he becomes swallowed up by the crowd. Demme holds on this shot as Shore's theme plays over the end credits, daring us to keep our eyes on Lecter. After a brief period, we lose him. He's successfully blended in with the rest of the crowd and society at large. Nobody would ever suspect he's an escaped cannibalistic serial killer. How could they? After all, he's dressed handsomely and professionally, no longer in a prison jumpsuit or muzzle. It's a heavily symbolic shot, with a message as transparent as it is unnerving. Serial killers like Hannibal Lecter could be walking amongst us every day. Sitting near us at a restaurant, walking beside us at a festival, living next door to us. And as long as they walk like us, talk like us, behave like us, and certainly dress like us, we'll never suspect the darkness lurking beneath the facade. Evil will be permitted to prosper. And that's the true horror of The Silence of the Lambs.

9.5/10

Comments

Post a Comment