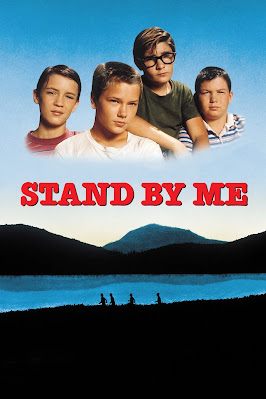

Stand by Me (1986)

Before I begin this review, allow me to address the gargantuan, corpulent elephant in the room: despite ironically materializing from the mind of Stephen King, quite inarguably the most renowned horror author in the universe, Stand by Me, a cinematic adaptation of a 1982 coming-of-age novella ominously titled The Body, is for all intents and purposes not a horror movie. Rather, it's one of the horror legend's relatively few horror-free excursions into the darker dimensions of the human mind and experience. Make no mistake, however, there are elements in Stand by Me that expose the DNA of King's affection for the genre that has defined him since he first composed the tragic story of a teenaged girl who used her telekinetic ability to exact vengeance on the town that belittled her her entire life: wandering out alone into the wilderness and coming face to face with an oncoming train, facing the wrath of bullies seemingly too large and in control to stand up to, coming to terms with the grim, inevitable ugliness of death. Stand by Me may lack conventional horror movie monsters, and the quartet of protagonists at its center may exit their journey with their young lives and limbs perfectly intact, but sometimes the most terrifying elements in life come from simply being alive and knowing our time comes with an expiration date. The sickening, dreadful thought of saying goodbye to the warmth and freedom of summertime as we re-enter the groan-inducing milieu of yet another 9-month school year is, in its own way, more harrowing than being chased through the woods by a machete-wielding, hockey-masked undead madman. Why? Because it's universally relatable and, up to a point in every child's life, unavoidable. And most distressing of all, drifting apart from the people we once considered our best friends to the very end. It's a heartbreaking reality for many, not all, but quite possibly most, including yours truly. This is the horror, the real brand of horror, that Stand by Me uncovers in unflinching detail.

There are too many adjectives I can use to describe my love for this movie, so for the sake of doing my best to avoid rambling (admittedly far from my strongest suit), I'll exercise some restraint and pick the ones that come to mind first. A quiet, warm, elegiac, powerfully moving, and emotionally resonant rumination on the euphoric freedom of childhood, the unmatchable beauty (and fragility) of friendship, and the inevitable ugliness of mortality, Stand by Me, adapted for the screen by best friends and writing partners Bruce A. Evans and Raynold Gideon, and brought to life by director Rob Reiner, is a bittersweet, timeless coming-of-age masterpiece with the rare power to warm the hearts and fill the tear ducts of filmgoers of all ages, backgrounds, genders, and time periods.

My introduction to Stand by Me came in the form of an episode of my favorite show, Family Guy, titled "Three Kings," in which creator Seth MacFarlane parodied a trio of Stephen King's most famous works. The first was this movie, and there was something that appealed greatly to me about the story, despite its freedom of overt horror elements. I was never a particularly adventurous person, but maybe this story tapped into that part of myself that I wish existed. A quartet of preadolescent male best friends taking a hike into the woods to discover a dead body came with the promise of an intriguing mix of adventure, camaraderie, and morbidity. Count me in. From that point onward, I had always kept Stand by Me in the back of my mind as a movie I'd like to watch at least once, should it ever appear on my TV (and my TV is pretty slow when it comes to playing old-time classics).

Then finally, on a Thursday night in early May of 2021, it made its first showing. Once it concluded, I thought what I usually do when I see a good non-horror movie: well, that was pretty good, got it out of my system, I'm ready to move on now. But then something happened that I could not have anticipated, that had never happened before or since: I wanted to watch it again the next night. Then the night after that. And probably the one after that. As of this writing, over four years later, I've watched Stand by Me more times than any other movie, horror or otherwise. While I lost count long ago, I'd estimate my number of viewings is well into the eighties, with my record being four nights in a row. And I do mean from start to finish each time. Never have I gone into Stand by Me and turned it off before reaching the end credits, nor have I entered past its opening frame.

Following my first handful of viewings, something else happened to me that had never happened before from watching a movie. I began to experience a sadness, a deep, visceral sadness in the pit of my stomach that all but obliterated my appetite and necessitated me to force myself to eat for about four days in a row. While anyone reading this might come to the instant assumption I was coming down with a virus or cold, I knew in the depths of my soul it was because of this movie, as silly as that may sound. Being a self-aware person, I determined to take a break from Stand by Me and engage in some self-reflection to understand why this single, not-even-90-minute motion picture had such a profound, physical impact on me. It didn't take long to arrive at the primary answer.

When I was a child, before I even entered kindergarten, my mother had become close friends with a trio of women whose children went to preschool with me. As a natural result, I became best friends with their children, who conveniently happened to be boys. While my memories of us as a group are hazy, I recall hanging out with them at playgrounds, a Gymboree called My Gym, and a pizza parlor named Raymond's. Most of those times are living eternally in a photo album stored in my basement. One night, our moms went to dinner at a restaurant where one of them announced she was expecting, and they made a promise to remain best friends forever. Lo and behold, things didn't work out that way, and just like that, I lost two of those mother's sons, never to see them again. Fortunately, my mom maintained her friendship with one of the three women, so by extension, I maintained mine with her son. Over the next several years, we made a lot of great memories together: going to the movies at AMC or Loew's after school, eating out for lunch at various fast-food restaurants, most notably Saladworks, Wendy's, and Pats Select Pizza, riding rollercoasters at Clementon Park, swimming at Haddontowne Swim Club.

Then one day, after spending time at the aforementioned amusement park, when this friend and I were around 10, his mother silently broke off with us. There was no fight between her and my mom, no friction. She just stopped calling us, with no explanation, and from that point, we have not once heard from or run into either of them. To this day, neither my mom nor I has received any closure. Oddly enough, in the beginning, that didn't bother me. My mom was deeply upset by the unexplained loss, but for years I was as indifferent as could be. I suppose my attitude was, "I have other friends. I don't need this one person in my life. It's just one less person to have to worry about seeing, right?" Like Richard Dreyfuss bluntly observes, "It happens sometimes. Friends come in and out of your life like busboys in a restaurant." And then I saw this movie at 22 and experienced a complete reversal of sentiment. Stand by Me permanently, drastically altered my perspective on that chapter in my life. It unlocked a sadness inside me I didn't know even existed. It reached through the screen, grabbed me by the shirt collar, and confronted me with the fact that I could have had a much better life if these three guys with whom I grew up had remained in it, at least longer than they did. Ever since, every second of every day, I think about these former friends and I loathe the fact that I lost them at such a young age. This movie galvanized me to do something I never would've even thought about doing otherwise: I went on social media and reached out to all of them, reminding them who I am and asking if we could talk. Sadly, they've all expressed, without saying it, a complete disinterest in reconnecting, but I try to keep hope alive that one day I'll run into at least one of them. Stand by Me imbued me with that longing and hope, which I never could have expected from a movie, and for that, while part of me thinks I should be resentful, I'm forever grateful.

Sitting in his jeep parked on the side of the road on a sunny afternoon in 1985, writer Gordon Lachance (Richard Dreyfuss) has received a devastating blow from a newspaper article detailing the recent murder of his childhood best friend, attorney Christopher Chambers. When two young boys cycle past his window, a flash of inspiration lights up his face. He is going to do something useful with this tragic revelation: channel it into his art. This serves as the framing device for the remainder of the movie, flashing back to a fateful Labor Day weekend in 1959 as Gordon reflects on a life-changing adventure he undertook at the age of 12 with his three best friends from childhood. 12-year-old Gordie (Wil Wheaton) lives in a small town in Oregon called Castle Rock. ("There were only 1,281 people, but to me, it was the whole world.") He spends the scorching Friday afternoon lounging in a self-made treehouse with Chris Chambers (River Phoenix), the leader of their gang and his best friend, and Teddy Duchamp (Corey Feldman), "the craziest guy [they] hung around with." Together, they pass their remaining hours of summer playing a card game and reading comic books. Bursting through the hatch is the chubby, excitable Vern Tessio (Jerry O'Connell), straining to catch his breath as he just ran all the way from his house. He has something urgent and shocking to tell them, insisting they won't believe it, begging them to tell their parents they're going to have a sleepover, but their responses are halfhearted at best. What could possibly be so important? As Gordie keeps his focus on his comic, and Chris and Teddy bicker over their cards, Vern drops the bombshell of a question: "You guys wanna go see a dead body?" The treehouse goes silent and all eyes are pinned on Vern.

At the beginning of the school year, he buried a quart jar of pennies underneath his house, drawing a treasure map so he could find them again. A week later, his mom cleaned out his room and thoughtlessly threw away the map. For the last nine months, he's been trying desperately to find them. Earlier that afternoon, while digging beneath his porch, Vern overheard his older brother, Billy (Casey Siemaszko), and Billy's best friend, Charlie Hogan (Gary Riley), arguing about their discovery of the corpse of Ray Brower (Kent W. Luttrell), a missing 12-year-old who went blueberry picking in the Back Harlow Road three days prior and was hit by a train. Rather than merely "see" the body, Chris conceives of the idea for the four of them to take credit for the discovery and get their faces plastered on the newspaper and TV, taking advantage of the fact that Billy and Charlie encountered the body in a boosted car. Eager to make their final weekend of the summer one they'll never forget and shed their shared status as outcasts in favor of being hailed as hometown heroes, the quartet of best friends embarks on foot on a two-day hike through the Oregon wilderness in pursuit of their fellow 12-year-old's dead body, but, to quote the philosophical Peter Griffin, what they end up finding instead is themselves... and also a dead body.

In terms of plot, that's about all there is to it, Evans and Gideon remaining commendably faithful to the blissful simplicity of Stephen King's source material. Four preteen boys hike into the woods to find a dead body, ultimately reach their intended destination, turn around, and head home. When you reduce Stand by Me to its barest of bones, the plot really doesn't sound all that exciting or complex. That's precisely the point. This story isn't about what happens, so much as it's about how the characters feel about what's happening: what's happening around them, what has happened to them in the past, and what's going to happen to them in the near, daunting future. Evans and Gideon take a simple, straightforward approach to their adaptation, and it's in the execution -- the writing, the acting, the visuality, and thematic profundity -- where Stand by Me excels and exerts its dominance in the coming-of-age drama genre. In the hands of less assured filmmakers exists a pitiful version of Stand by Me where the protagonists stumble across a space ship that's crashed into the forest containing an alien that wants to return to its home planet, and it's up to these four young nobodies to ensure that happens. Fortunately, Evans and Gideon trust in the natural beauty and adventure inherent in real life, without feeling obligated to shoehorn in fantastical, supernatural, or science fiction elements to make their story more "cinematic."

Throughout the course of their characters' weekend journey, there are only two significant conflicts: a run-in with a petty man-child of a junkyard owner named Milo Pressman (William Bronder) and a teenaged gang of juvenile delinquents led by town bully Ace Merrill (Kiefer Sutherland). Evans and Gideon narrow their focus intimately on their protagonists, following their arduous physical trek through the woods and detailing their emotional growth as they leave behind their unfulfilling lives in Castle Rock and experience a first taste of the coldness and uncertainty of the merciless real world. On the few occasions where the filmmakers deviate from their journey, it's for the purpose of catching up with the older gang to detail the more mischievous ways in which they're spending their final days of summer vacation -- playing mailbox baseball, speed racing, lounging on top of cars and carving their group name into each other's arms with a razor blade -- so Stand by Me maintains the feel of a hangout movie through and through. Never for a second are we subjected to an extraneous subplot in which the parents of the boys come together and realize their sons lied to them regarding their whereabouts.

Counterbalancing the simplicity of the bare-bones premise are the heavy real-world themes woven into the fabric of the script. Even better, Evans, Gideon, and Reiner wed these themes to their characters to invest them with greater staying power. By the end of the movie, a lot more has happened, internally speaking, than four friends simply finding a dead body. Coping with the loss of a loved one; feeling unloved and unwanted by your parents, who openly favored your older, more financially promising sibling; facing unpredictable physical and emotional abuse from an alcoholic father and delinquent older brother; the effects of war-fueled PTSD transferred from a mentally deranged father to their impressionable, naive offspring; feeling permanently handicapped by a poor familial reputation; and coming to terms with your own mortality. Stand by Me is, on the surface, a breezily entertaining boys' adventure into the peaceful, occasionally ominous unknown of the woods, but once the screen fades to black, it leaves us with plenty of food for thought, including, most interestingly of all, a polemic against serving in the military. Teddy may glorify the bloodshed, gunplay, and cacophony of combat, but neither the screenwriters nor the director do.

Much like the moment Gordie, Chris, Teddy, and Vern discover Chopper, "the most feared and least seen dog in Castle Rock," is not some oversized, sharp-toothed, testicle-snatching beast, but rather a normal-sized, adorable Golden Retriever with more bark than bite, the filmmakers explore and delineate the vast difference between myth and reality. At the beginning of the story, when the boys first vocalize their idea to hike into the woods and find Ray's corpse, and their plan is nothing more than an abstract concept, Reiner and his actors infuse the tone with the lightheartedness and irrepressible energy of youthful ignorance. What better way to eat up their final weekend before entering the intimidating unknown of junior high than to pack some sleeping bags, venture into the serenity of the wilderness, and return as heroes, rubbing it in the faces of those who have judged and undermined them? However, once the reality of their morbid destination begins to gradually sink in, hovering over their heads like a dark raincloud preparing to burst, the story takes on a much heavier and more sobering tone. "I'm not sure it should be a good time," wisely opines Gordie. "Going to see a dead kid, maybe it shouldn't be a party." By the time the quartet uncover the face of their target, and experience up-close what death really looks like, how it's nothing to get excited about, but to approach with dignity, reverence, and melancholic acceptance, Reiner and his cast deliver a punch straight to the solar plexus, a splash of ice-cold water to a previously sweat-drenched face.

Despite being only twelve years of age (in terms of character, if not necessarily individual performer), the quartet of protagonists around which Stand by Me revolves consists of well rounded, fully dimensional individuals with thoroughly distinguishable personalities, mannerisms, home lives, and traumatic struggles. From the instant of their introduction as a group, Gordie, Chris, Teddy, and Vern cease to be mere figures in a fictitious screenplay and instead become something much deeper. You could never confuse one with the other. They are individuals in every sense of the word. When I watch Stand by Me, I'm not just watching the adventure of these guys from the opposite side of a screen; rather, I'm attending this adventure alongside them. Reiner transports us to this quiet, sunny small town within this far simpler time period of innocence, in the company of the four greatest friends I never fully had at any point in my life, no matter how close I came, and desperately wish I had. Without undergoing anything particularly earth-shaking during their weekend odyssey, the people these four kids are at the beginning of their journey are infinitely different from the people they return home as. Fundamentally, they are still the same lovable, goodhearted goofballs at heart, but with a renewed perspective on the world, a more clear-eyed attitude toward death, and a much greater developed sense of integrity, what it means to be a good person. To do not what will enhance their reputations in the eyes of the townsfolk, but to do what is morally right. Along the way, they each discover their own inner strength and respect for themselves as well as each other.

While Stand by Me is by and large a drama, Evans and Gideon sprinkle in a dash of lighthearted humor to help their narrative resonate with audiences both young and mature, and it's through the art of dialogue that they communicate their comedic dimension. As expected from a story about four friends going on a two-day excursion in the woods, Gordie, Chris, Teddy, and Vern spend the bulk of their screen time walking and talking among themselves, and it's in their interactions where the source of the true magic of Stand by Me lies. Evans and Gideon pepper their characters' dialogue with the witty, lived-in banter appropriate for preadolescent boys who've been temporarily set free from the oppressive constraints of their parents and left to their own devices, in the private company and mutual support and platonic love of one another. Unsurprisingly, the bulk of the writers' acidic wit is leveled almost exclusively against poor baby-faced Vern, who is forced to bear the brunt of his friends' most devastating one-liners and put-downs, particularly from the aggressive Teddy. Therefore, it's to Evans and Gideon's credit that they manage to keep their banter good-natured and creatively biting without crossing the line into outright mean-spiritedness which would leave us questioning why and how Vern could ever be friends with them. Furthermore, it would be easy to make Vern's weight the butt of the jokes. After all, he is the only (moderately) overweight member of the group. But these writers are too respectful, clever, and thoughtful for such a cliche, instead centering their verbal daggers around Vern's personality, his simplicity, his sometimes aggravating but mostly endearing innocence and timidity. It makes all the difference.

The pithiest and wittiest dialogue would fall flat, however, just words written on paper and spoken from the mouths of humans, without a cast who could deliver it with the naturalism, charisma, and lived-in quality crucial to making it pop. Thank the moviemaking god that is Rob Reiner for assembling such a stellar, masterfully selected and assigned cast. In a 2011 interview with NPR, Wil Wheaton attributed Stand by Me's success to his director's instinctual casting choices: "Rob Reiner found four young boys who were the characters we played. I was awkward and nerdy and shy and uncomfortable in my skin and sensitive, and River was cool and smart and passionate and even at that age kind of like a father figure to some of us, Jerry was one of the funniest people I had ever seen in my life, either before or since, and Corey was unbelievably angry and in an incredible amount of pain and had a terrible relationship with his parents." Before filming commenced in the summer of 1985, Reiner strategically put the central quartet of actors together for two weeks to play games from Viola Spolin's Improvisation for the Theater and establish a legitimate camaraderie. It was a strategy that paid off in spades, as their chemistry translated effortlessly from the screen. When they converse on-camera, it doesn't have the artifice of young, inexperienced actors reciting lines from a script. It feels like four real-life best friends having an impromptu conversation and basking in the joy of their early youth and seemingly impenetrable brotherhood. That's because, regardless of the brilliantly written script at their disposal, it was. As Wheaton would later recall, "When you saw the four of us being comrades, that was real life, not acting." The on-camera friendship between these characters is so much more affecting because it started off-camera between the actors inhabiting them, and continued long after the cameras stopped rolling.

Although Stand by Me is technically an ensemble piece, Reiner and his adapters made it a point to center King's story around Gordie, framing it as a remembrance from his adult memory and depicting events through his vulnerable eyes. As a result, Gordie is the audience surrogate, the character whose perspective we witness this world from. He is also the character with whom I identify the strongest. Like Gordie/Wheaton, I've always struggled with feeling uncomfortable in my own skin, sometimes to the point of wanting to rip free from it. I've always been the shy one in a group of people my age, especially if it consists of people I don't personally know. Afraid to talk, not knowing what to say, where to sit, where to stand, if I should do either. I'm a walking example of social awkwardness at times. This makes Wheaton's outstandingly contained and withdrawn performance a treasure of heartache and comfort. He plays Gordie with the quietest and least showy personality of his friend group, simply going with the flow with a slight shrug and indifferent "Why not?" casualness of tone. But beneath his placid exterior lies an exceptionally gifted kid carrying the weight of suppressed grief and loneliness on his underdeveloped shoulders, a weight no child his age should have to carry, at least not on his own.

Four months prior to the events depicted onscreen, Gordie's older brother, Denny (John Cusack), with whom he shared a close relationship, was killed in a jeep accident. All summer, he's taken on the role of "the invisible boy," as his parents are so crippled by their grief they seem to have forgotten they still have one son left (not that they paid him much attention beforehand). Gordie accepts their negligence with a mature, respectful understanding, never one to make waves, but one look into Wheaton's soulful eyes and you can see how deeply he's suffering in silence, physically surrounded by friends but internally all alone in a private hell. He possesses a talent for writing, but because he's been convinced by his father that it's "a stupid waste of time," likely owing to its low prospects for financial success, a fear I myself can relate to daily, Gordie internalizes feelings of worthlessness, until all those pent-up frustrations and insecurities burst forth in a cascade of tears following the encounter with Brower's lifeless, bloodied face. This cathartic moment, where Gordie breaks down over his father's indifference toward him and is comforted in the arms of Chris, is my favorite scene in a film whose practically every scene I worship, a patient, heartfelt, bravely unrestrained depiction of the type of camaraderie and affection that escapes most men once they reach the more judgmental and homophobic waters of adulthood. Adding further resonance is the fact that I experienced a moment thrillingly similar with my best friend when we were 19. One night, while we were sitting on the couch in our friend's apartment, my friend, who at that time was in the throes of alcoholism, suddenly broke down in tears over a miscellany of woes, and I reacted in an identically instinctive manner to Chris, embracing him and granting him the breathing space to vent. As Gordie's desire to stare death in the face and come to terms with that of his brother grows into an indescribable obsession, Wheaton develops a newfound assertiveness and transitions convincingly from a soft-spoken, put-upon wallflower to a take-charge, gun-toting, no-nonsense warrior who refuses to be stepped on by the bigger kids any longer.

While there can be little debate that Gordie is the protagonist of Stand by Me, and the role for which Wheaton will justifiably remain best remembered, Chris Chambers is the fan favorite, and River Phoenix the MVP. On the night of October 30th, 1993, Phoenix suffered a grotesque, painful seizure at the age of 23 on the sidewalk outside a Hollywood night club, going into cardiac arrest and passing away early Halloween morning due to "acute multiple drug intoxication." Before his fatal addiction claimed his life, Phoenix had left behind an impressive career in acting and music, earning a single nomination for Best Supporting Actor for the drama, Running on Empty, in 1989. It will always be a mystery how much more success he would have achieved if he were still alive today, how many other nominations he might have gotten, maybe a win or two. While there's no use in dwelling on the unknowable, Phoenix can rest comfortably and peacefully in the knowledge he will always be remembered most for his beautiful co-leading performance as Chris, the greatest best friend a person could only hope to have at at least one point in their life. When he isn't taking a breath in the safety and companionship of his bros, Chris is forced to contend with a miserable home life populated by the most toxic of male role models. His father is a physically abusive drunk prone to bouts of unpredictable anger, and his older brother, nicknamed "Eyeball" (Bradley Gregg, who one year later would become Freddy Krueger's human puppet in A Nightmare on Elm Street 3: Dream Warriors), is the second-in-command of Ace's greaser gang who takes pleasure in watching his friend threaten to put out his cigarette in his little brother's eye. And yet, against all odds, by the grace of God or nature, Chris is the polar opposite of his relatives, so much so that one wonders how he isn't adopted. He literally saves Teddy's life two times (three, if you count a deleted moment during the boys' walk across the train tracks) when his reckless displays of machismo nearly get him killed, and he assumes the role of the father figure he doesn't have and that Gordie needs, nurturing his talent for writing now that Denny is no longer around to.

Sliding into the role as though it were a tailor-made sweater, Phoenix projects leadership, intelligence far beyond his years, perception, compassion, empathy, and a paternal tenderness, never more evidently than in a hard-hitting dialogue with Gordie en route to the tracks in which he counters the latter's age-appropriate denial toward the future with a more resigned outlook -- juxtaposed comically with a well-timed cutaway to a frivolous debate between Vern and Teddy about who would win in a fight between Mighty Mouse and Superman (the 12-year-old guy logic in the answer makes a hell of an argument). However, to refrain from reducing Chris to a one-dimensional peacemaker and angel sent down to earth to be a friend to those who need him, Phoenix and the filmmakers take care to flesh him out into a three-dimensional human being with his own desires, insecurities, and shortcomings. In his most revealing moment, while Chris is sitting against a tree under the blackness of night, the only person beside him his best friend, Teddy and Vern asleep around a campfire, he bares his soul about a betrayal from a teacher that has all but confirmed his worldview that the fate of his life has already been determined by those who know nothing about him, condemned to a mediocre life trapped in Castle Rock by the white-trash delinquency of his family. Chris sees the intelligence and talent in Gordie that he's unable (or unwilling) to see within himself. He wishes he could leave town and "go someplace where nobody knows [him]," but he's allowed the people around him to make him feel like that's not an option and never will be. Overwhelmed by feelings of inadequacy and powerlessness, but safe in the lack of judgment of his best friend, Phoenix obliterates the walls he'd built up and exposes in close-up the vulnerable little boy protected by the smart-mouthed, cigarette-smoking group leader, his voice cracking with the pain of a child who knows deep down he's a good person but can't get anyone else to believe him, a spray of snot shooting out his nostril as he breaks down crying into his own arms.

At first glance, Phoenix sports a classical tough-guy appearance -- short light brown hair brushed up at the front, a loose white T-shirt tucked into high-waisted cuffed jeans, and a pack of cigarettes rolled into his right sleeve -- only to quickly subvert it with a softhearted interiority. In his second scene, Chris takes comedic pleasure in Gordie accidentally shooting a bullet at a trashcan, having been told by Chris that it wasn't loaded, but the second Gordie accuses him of knowing the gun was loaded, Chris, unable to bear the thought of his best friend thinking he's that type of person, stops Gordie in his tracks and swears he didn't know. Phoenix conveys the utmost sincerity sincerity in his guileless eyes, soft voice, and close-mouthed smile, and gives Chris a demonstrative physicality by constantly smacking a hand on a friend's shoulder to establish peace or wrapping an arm around the shoulder of a friend in distress.

The friendship between Gordie and Chris represents the heart and soul of Stand by Me. While it's never explicitly stated, and Chris' loyalty to and protectiveness over all of his friends are never in question, it can be safely inferred that these two became best friends long before either of them met Teddy and Vern. It's apparent in the way they smile at each other while panting from a race to a water pump and the revelation that their friendship continued into their college years, long after Teddy and Vern become "just two more faces in the halls." Speaking of those two, Vern and Teddy are like water and oil, yet they go together in spite of their contrasting personalities.

Teddy is the most psychologically damaged of the group, a rambunctious tyke whose father, a former WW1 veteran who, as Teddy proudly boasts, stormed the beach in Normandy, held his ear to a stove and nearly burnt it off in a fit of rage. Consequently, he was confined to a mental institution. Nonetheless, Teddy misguidedly reveres his father as a model of masculine pride and aspires to follow in his footsteps by enlisting in the army when he's of age. Fresh off the success of his iconic supporting performance as Jason Voorhees' unlikely slayer, Tommy Jarvis, in Friday the 13th: The Final Chapter, Corey Feldman delivers the performance of his career as Teddy Duchamp. Undeterred by his round, metal-rimmed glasses, disfigured left ear, and hearing aid, Feldman plays Teddy in a manner that lives up to the narrated descriptor spoken at his introduction. He's the craziest and most unapologetically alive of his comrades, unafraid to live life to the fullest and embrace his youth while he still has it. It's therefore fitting he's given one of the best lines to summarize this key theme: "This is my age. I'm in the prime of my youth, and I'll only be young once." Never once does Feldman ask us to feel sorry for Teddy. He is who he is, and he loves himself. Feldman captures Teddy's youthful exuberance from the moment he arrives on scene in the middle of a card game, his eyes wide and manic, an ear-piercing, almost witchy cackle escaping his mouth at someone else's misfortune. He speaks in the military jargon of someone who seems to forget he's not yet in a warzone, but feels so close he can taste it.

However, no matter how hard he tries to put his past trauma behind him and live in the illusion that his father is a hero, two scenes unveil a much darker side to Teddy. The first is when he attempts a game of chicken with an oncoming train, utterly confident in his ability to dodge it. His eyes widened with deranged fervor, his mouth uttering the sound of bullets as if he's transported himself to the beach in Normandy, Teddy flies into a physical rage when Chris forcibly picks him up and removes him from the tracks before he can get hit. It's here where Feldman first grants us access into his unstable mind and disregard for his own life. Does Teddy lash out at Chris because he bruised his fragile ego, or because he was subconsciously hoping the train would win? Feldman does a phenomenal job playing up the ambiguity of the moment. Once Teddy is confronted with the harsh reality of his father's condition, Feldman's carefully cultivated veneer of devil-may-care machismo and bravado cracks in the snap of a finger, unveiling the deep-seated torment and fury he'd been masking from his friends all along.

Vern is the biggest outlier of the gang, not just because of his weight, which is impressively not brought up save a single jab at a pond. No, he stands out from the other three guys by way of being refreshingly drama-free. Unlike Gordie, Chris, and Teddy, Vern doesn't have anything particularly negative going on at home. Sure, his older brother is part of Ace's gang along with Chris', but aside from one instance when Billy threatens to strap him with a belt for eavesdropping, nothing indicates Vern gets abused on a regular basis. His biggest struggle in life is being forced to eat his lima beans. We neither meet his parents nor hear anything good or bad about them. This lack of trauma, abuse, and negligence accounts for his personality being the most chipper and unsophisticated. By the conclusion of their adventure, Vern is the only character who doesn't experience a tearful breakdown, despite ironically often being derided as a "pussy" by the more macho and fearless Teddy. It's that very simplicity of upbringing and lifestyle that distinguishes Vern and makes him a great character in his own right. Though the characters are all implied to be the same age, Jerry O'Connell is in actuality the youngest of the quartet at 11, and he uses that to his advantage. Vern very much registers as the baby of the group because O'Connell leans into his perceived flaws with a childlike gusto. From the moment he bursts through the hatch of the treehouse, huffing and puffing with excitement and exertion, O'Connell becomes the character, playing Vern as a cheerfully clueless and endearingly naive soul who appreciates the little things in life, like finding a stray penny to add to his collection on the street.

Armed with the bright smile and chubby cheeks of a happy-go-lucky cherub eager to be included, and the high-pitched voice of someone for whom puberty is a few years in the distance, O'Connell provides the comic relief with his bumbling clumsiness and unconcealed timidity that often put him at odds with his more courageous friends, but he's talented and perceptive enough to define Vern as a full-fledged human being as opposed to a caricature or punch line, maintaining his humanity even when the script occasionally veers toward condescension. At one point, during a particularly arduous stroll, Vern is elated at the thought of having finally gained the upper hand over Teddy in their habitual one-way game of "Two for Flinching." However, Teddy breaks the rule at the last second, and the look of confusion on O'Connell's face is priceless. He imbues Vern with dignity and a guileless charisma that earns our affection even as he unintentionally evokes the annoyance of his comrades. Vern is simple but rarely simple-minded. O'Connell's most gratifying moment occurs toward the climax when Vern suddenly develops a backbone and stands up to Teddy (in his own characteristically awkward way) after being called the P-word one too many times.

An adaptation of a Stephen King story wouldn't be complete without a gang of bullies dominated by one especially coldhearted psychopath armed with a trusty switchblade, and Stand by Me is no exception. In this case, we have Ace Merrill, portrayed with devilish glee and charisma by Kiefer Sutherland. From the moment he emerges from a pool hall, Eyeball loyally by his side, and casually snatches the Yankee cap off Gordie's head, flashing a sadistic smirk as Gordie reaches in vain to reclaim it, Sutherland announces Ace as a uniquely heartless and narcissistic villain unlike many others. This is not your average over-the-top bully who wears a leather jacket, has jet-black hair slicked back, and froths at the mouth when he doesn't get what he wants. Nor does he go around single-mindedly looking for fights and an excuse to flip his blade upward. Compared to other villains in the King catalogue, like the one-dimensional Henry Bowers, whose sole purpose in life is to murder (by switchblade, of course) every member of the Losers Club, or Chris Hargensen, who's driven by an insatiable thirst for vengeance against Carrie White for "getting her banned from prom," Ace comes across as almost low-key, a guy who just wants to kick back with his fellow greasers, commit some petty vandalism for fun, and only pick on kids who are smaller should they present themselves. He doesn't go out of his way to physically harm anybody. However, Ace fits the definition of a malignant narcissist to a T, someone who invariably feels the need to be in control of everything and everyone around him. It's either his way or the highway (and even that's debatable).

In his first major motion picture role, Sutherland exudes quiet menace, using a calm but unmistakably authoritative voice to exercise dominance, whether over his younger counterparts or his own "friends." Sutherland plays Ace as someone who's gone through life always getting what he wanted, never meeting anybody daring enough to tell him, "no." At no point is his narcissism and selfishness more apparent than when he finds himself sharing the street lane with an oncoming log truck while Billy and Charlie are seated beside him, imploring him to fall back. Sutherland's eyes shine with a demented concentration and nonnegotiable determination as he chews on a toothpick while his horrified friends scream for their lives. To no surprise from Ace, the truck swerves off the road and loses multiple logs in the process, enabling him to cut in front of his friend, Vince Desjardins' (Jason Oliver Lipsett) car during their race. "I won," says Ace, taking a self-congratulatory sip of beer. That's all that ever matters to him: winning.

All of that is getting ready to change as, for what appears to be the first time in his young thug life, Ace will find himself in a power struggle in which he will not emerge victorious. During the quietly tense standoff between the older and younger gangs, both gathered around the body of Ray Brower, vying for the credit of discovery, Ace comes face to face with the paralyzing barrel of a gun. Sutherland is incredibly nuanced in this scene, conveying the universal human fear of death while struggling mightily to maintain the illusion of control. Once Ace finally realizes the reality of the situation, that now he is the log truck he previously forced off the road and must himself relent, Sutherland inwardly seethes at the slight to his hitherto unquestioned authority, registering humiliation and rage on his face without raising his voice by a single octave. Instead, he raises his knife and softly declares, "We're gonna get you for this!" before calmly walking up the hill from which he came down, empty-handed and crestfallen. It's a brilliantly composed and laid-back portrayal of refreshingly understated villainy.

Before settling on Richard Dreyfuss for the dual role of adult Gordon and the narrator (same character, separate functions), Reiner considered three lesser known actors: David Dukes (whose profile is visible in the opening exterior shot of Gordon's jeep), Ted Bessell, and Michael McKean. While I can't personally speak on the talent of those three, I also can't imagine a version of Stand by Me in which Dreyfuss isn't the character. Physically, he's only present in two bookending scenes, one pre-flashback and the other post-flashback. With few lines of dialogue and even fewer actors to play off of, Dreyfuss accomplishes so much with remarkably little material, utilizing his beautifully expressive face to deliver a contemplative performance of the utmost restraint. While sitting in his jeep and processing the news that his best friend from childhood, who he hasn't seen for ten years, is now gone forever, Dreyfuss conveys such silent devastation and regret in his face and the fidgeting of his fingers. No tears or audible whimpering are even necessary. In both of his on-camera scenes, when an important idea manifests in his mind, he enables us to see the light bulb shining brightly behind his eyes. When he reflects on all that he's accomplished in his journey from childhood to adulthood, Dreyfuss flashes a smile of contentment, emitting a soft breath of gratefulness. As he stands up, prepared to turn off his computer and follow through on a promise to his son, he takes a moment to stare at the final line in his latest work, possibly the best and most profound line in the movie, one that speaks to an agonizing universal truth. He reflects on the line, smiles at it, feels satisfaction with it.

In between these scenes of masterful near-silent acting, Dreyfuss serves as the narrator of the story, and his vocal performance is just as integral and indispensable as his facial one. Of course, it helps that the lines written for him to recite in voiceover are flat-out brilliant. Evans and Gideon employ their narration sparingly to deliver universally relatable observations on the human condition ("Everything was there and around us. We knew exactly who we were and exactly where we were going. It was grand.") and add extra depth to certain scenes (including Gordie's silently magnificent encounter with a deer) without falling back on it as a crutch to fill in details they failed to properly visualize, spell out things we can see unfolding before our eyes, or most egregiously of all, spoon-feed us subtext they didn't trust us to eat on our own. Dreyfuss doesn't just read these non-diegetic lines; he invests them with warmth, wry humor, and a touch of wistfulness, reflecting on his past with a mix of world-weary sarcasm for the silly behaviors of yesteryear and a genuine longing and reverence for the simpler, carefree days of childhood innocence that have long since passed.

Even though John Cusack only appears in two posthumous flashbacks, he brings the Everyman heart and charm that would turn him into a Hollywood heartthrob and leading man further down the road. While Denny has been deceased for four months prior to the events of Stand by Me, Evans and Gideon refuse to lazily leave him as a mere memory in Gordie's heart. Instead, they utilize his two scenes to flesh him out into a key figure in the story, establishing the affectionate brotherly bond he shared with Gordie so that the impact of his death is felt just as keenly by the audience. In his first scene, Denny gifts Gordie his good-luck Yankee cap (the one stolen by Ace), explaining it'll help them catch "a zillion" fish, and envelops him in a hug. In his second, the Lachance family is gathered around the table eating dinner, and while their father (Marshall Bell) is lavishing attention and admiration on Denny for his upcoming football game, he modestly shifts the spotlight to his younger brother, praising a story he recently wrote. For the present, Reiner and his set designers adorn Denny's bedroom with memorabilia -- logos of Michigan State University, a framed photo of Denny in his quarterback attire holding a football and posing with his prom date -- to paint a poignant picture of a promising young life cut tragically short.

In its own quiet, serene fashion, Stand by Me is paced to the effect of a rollercoaster: fast, exhilarating, and once it's over, all you want to do is get right back on. Almost as soon as the boys commence their journey, they wind up at the Royal River, which accelerates them to their destination. Clocking in at a svelte 89 minutes, there is not an ounce of excess fat on the bones of Evans and Gideon's emotionally intelligent script. No walk through the woods or informal conversation drags on for a second. Reiner and his editor, Robert Leighton, present their story concisely and accomplish a most remarkable feat in the process: ensuring the runtime zooms by without cheating us out of hard-earned character development and interaction. They spend just enough time with their characters and provide the breathing space for them to let their guards down and expose themselves emotionally naked so that by the end of the trip, we come to know them inside and out as our own friends.

Cinematographer Thomas Del Ruth makes Stand by Me just as aesthetically intoxicating as it is emotionally, saturating nearly every last frame, both wide and tight, in the baby blue of the cloudless sky and the vivid green of an abundance of trees and grass. He utilizes extreme wide shots to capture the austere grandeur of mountain and river scenery, none more captivating than one that reduces the quartet to four black stick figures as they cheerily sing "The Ballad of Paladin." Whether intentionally or not, the clothing worn by the central cast, in particular their cheerfully colored T-shirts, accomplishes the dual benefit of distinguishing their characters physically as well as feeding into the striking color palette. Jack Nitzsche composes a somber incidental score that accentuates the melancholy of the script's more serious moments without ever threatening to overwhelm them, the most haunting use occurring when the boys take their silent, dejected walk back to Castle Rock through the forest. By contrast, Reiner has compiled an upbeat soundtrack populated by 1950s and early 1960s oldies songs. In addition to grounding Stand by Me in its 1950s era (serving as the only element that reminds viewers this story takes place in the past), Reiner judiciously selects songs that accurately express the mood of the scenes in which they're seamlessly integrated. For example, when Ace and his gang are spreading havoc throughout their town, Reiner plays "Great Balls of Fire" by Jerry Lee Lewis and "Yakety Yak" by The Coasters to complement their tomfoolery. When the protagonists set up camp around a campfire and swap memorably meandering remarks, Reiner serenades us with the soothing ballad, "Come Softly to Me," by The Fleetwoods. (The sound mixing is flawless, playing the song at a low hum in the background so as to emphasize the serenity without drowning out the cast's dialogue.)

Evans and Gideon reserve the slapstick for two inspired set pieces. The most overtly comedic is the imaginary "barf-o-rama," whereby Gordie entertains his friends with a story he's been contemplating about an overweight outcast named Davey "Lardass" Hogan (Andy Lindberg) who enters a pie-eating contest with the ulterior motive of exacting vengeance against the people in attendance. Using pies and extra filling mixed with large-curd cottage cheese supplied by a local bakery, Reiner goes all out on the juvenile, over-the-top gross-out humor in this fantasy, not for the sake of eliciting cheap laughs, but to illustrate the boundless, uninhibited imagination of its 12-year-old author. Even more effective (and affecting) than this brightly colored and energetically directed interlude is a shot the succeeds it: returning to the tangible story, Chris, Teddy, and Vern erupt in cheers and claps of vicarious triumph, and Gordie breaks out in a slight smile of validation that reads, "Wow, maybe I can really do this." The following morning, the boys fall into a pond after misjudging its depth, and a brief moment of improvised bonding and turning lemons into lemonade quickly curdles into a cringe-inducing display of comedic body horror as they find themselves covered from neck to testicles in leeches, a credible outcome given their situation. As they frantically strip down to their underwear and rip the leeches off their skin, Leighton conveys their panic with a series of quick cuts.

Despite its overall departure from its creator's favorite genre, there is one set piece that reflects Stephen King's penchant for horror. That, of course, is the iconic train scene in which the protagonists nearly meet the same fate as the boy whose body represents their impetus. Filmed on the McCloud River Railroad, above Lake Britton Reservoir near McArthur-Burney Falls Memorial State Park in California, the scene took a full week to shoot and employed four small adult female stunt doubles with closely cropped hair who were made up to resemble the central male quartet. Telephoto compression was used to create the illusion of the train being much closer to the characters than in actuality. At the start of filming, the actors failed to muster a legitimate sense of terror, so Reiner attempted an audacious tactic: he resorted to threatening them, saying, "You see those guys? They don't want to push that dolly down the track anymore. And the reason they're getting tired is because of you... I told them if they weren't worried that the train was going to kill them, then they should worry that I was going to. And that's when they ran." Evidently, it was a move that paid off perfectly, the heart-pounding fear, urgency, and desperation to survive palpable, especially from Wheaton and O'Connell, the latter of whom breaks out in an authentic cry that adds extra realism and pitch-black humor to the horror. Reiner prolongs the arrival of the train to build suspense, cutting between close-ups of the railroad metal, shots of empty space at the front of the railroad, and scenery shots of the boys walking carefully across the tracks. Once the train makes its inevitable appearance, Reiner milks the moment for every possible drop of tension, blending nerve-racking dread and physical humor with razor-sharp editing and painstaking shot selection (medium shots of the actors, wide shots to conceal the identities of the stuntwomen, ground-level shots of legs running at lightning speed) to produce a set piece that's at once darkly humorous and genuinely terrifying.

The ending is perfectly imperfect in a way that accurately reflects real life. It marries an uplifting message of hope with a hard-hitting dose of realism. It's neither entirely happy nor tragic, but somewhere in between. Evans and Gideon acknowledge that if you work hard and refuse to allow yourself to be held down by other people's opinions and expectations, you can achieve your wildest dreams. There's no limit on your own life. But they also wisely point out that not everything in life gets to work out swimmingly for everyone. They don't betray the integrity and emotional honesty of their story with a fairy-tale resolution. True to the tautness of the preceding 80-plus minutes, the fates of the protagonists are encapsulated in a few sentences of narrated exposition that tell us just enough and a single scene set in an author's study. Like the cherry on top of a flawlessly baked and designed cake, it's topped off with the perfectly chosen and timed titular song by Ben E. King, whose "Stand by Me" not only gifts the adaptation its title but more importantly reflects its core themes of friendship and the value of sticking together in the toughest and most uncertain of times.

If a 10 out of 10 rating simply indicated my favorite movie, the movie I've watched more times than any other and can quote nearly verbatim, then Stand by Me would be a 10 out of 10 every time, no question. But for the sake of maintaining my critical integrity, there are a few nitpicks I can make and would be lying if I claimed not to notice. For starters, Gordie's father is a one-dimensional asshole who markedly lacks a before-and-after contrast. When Denny was alive, he still expressed zero interest in his younger son's talent and berated his wife for daring to insert herself in their supposed "family" dinner conversation. Secondly, Kent Luttrell, who more or less portrays the corpse of Ray Brower, is visibly too old to pass for a 12-year-old. Remember, the protagonists set out to find him not just because they're eager to feast their eyes on any dead body, but specifically the body of a kid their very age. This is someone who could literally be their friend, their brother, themselves. His age isn't a throwaway detail. It's integral to the characters' motivation. So it's distracting, not to mention undermining to that underlying psychological ache, to look down at the lifeless face of this decomposing corpse and see a 20-year-old man beneath the admittedly spot-on makeup effects of caked blood and bruising. This represents Rob's only head-scratching misstep in casting. You're telling me he couldn't find an actual kid closer to Ray's age to lie down and play dead for one scene? On a pettier note, some of the ADR is a bit clumsy, notably in Vern's introduction where the movement of his lips fails to sync with the words supposedly exiting his mouth, and in the shot where Chris and Gordie run behind the Blue Point Diner: Wheaton's mouth is moving, but his lines have been excised. Lastly, as previously mentioned, a simple edit could have solved the visible profile of David Dukes in the opening exterior shot.

With that handful of "flaws" comfortably out of the way, Stand by Me is a practically perfect motion picture. It's so much more to me than a mere motion picture, a passive way to kill an hour and a half. It would have to be, because I'm not a fan of cinema in general. This is a once-in-a-lifetime jewel that sits on an entirely separate plane of significance. A warm, comforting blanket in the form of a movie. A loving, prolonged hug from the best friends we have for life, lost a long time ago, or never truly had. A singularly transportive journey to a small town in a peaceful time period in which I feel remarkably at home (despite the lack of technology). Stand by Me is a microcosm of the trials and tribulations of growing up and apart from the people we once considered thicker than blood. It's about the loss of innocence and the gaining of wisdom and integrity. An unethical quest for fame that evolves into a journey of shared self-discovery. A story whose seemingly minuscule details contribute greatly to its gargantuan cumulative emotional impact; the odyssey doesn't take place on a random weekend in the summer, but specifically Labor Day weekend, two of the final four days of summer vacation. And the preteens aren't facing another year of grammar school, they're getting ready to enter junior high, a new academic stage guaranteed to separate them by the following June according to their individual intelligence levels. It's narratively simple but emotionally complex. Superficially lighthearted and quietly exhilarating yet thematically loaded. Wistful yet clear-eyed. Witty and warm yet delicate. Optimistic and uplifting yet gut-wrenching. Stand by Me will obliterate your heart into a zillion pieces and put the biggest, sloppiest smile on your face at the same time. Sincerely.

9.6/10

Comments

Post a Comment